BRIG O’ TYNE

• A Duffy Whitmore Adventure *

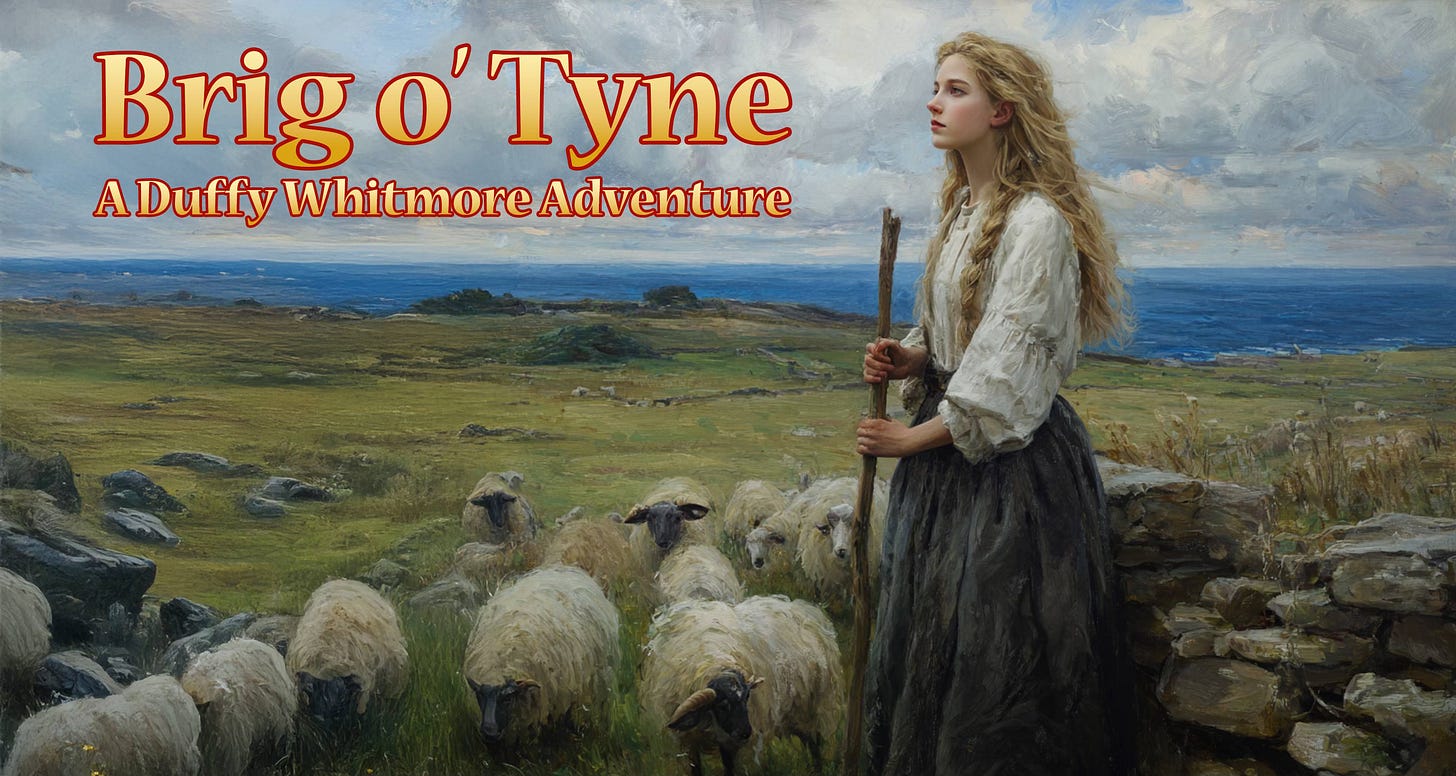

Part I — The Shepherdess of Time

(June, 1930 — or thereabouts)

It was Lord Thornton’s idea, of course. Known to us as “Ruffles,” he announced one morning that he required a first-class Border Collie — blue-ribbon pedigree, the sort of creature that could fetch the newspaper and then lecture on Plato if pressed. And he knew precisely where such paragons were bred: by his cousin, Sir Roger Scholefield, at Tyneholm Park, a thousand-acre estate through which the River Tyne ambles like a strip of tarnished silver.

Sir Roger’s hobby was raising Border Collies for the local shepherds — dogs of exquisite manners indoors yet ruthless efficiency out on the hills. To Lord Thornton, that combination of elegance and discipline sounded ideal. “Rather like Kamau,” he remarked.

Kamau, unruffled as ever, merely inclined his head.

Letters and Invitations

A letter went north.

Lord Thornton: “I hope you’ll accept a few friends as guests. It’s been ages since I’ve seen the lads. They’re both in the U.K. just now, so it’ll be a merry gathering.”

The reply came by telegram that evening:

Sir Roger: “The more the merrier. Keen to hear of these baffling slips in time you fellows keep encountering.”

The Lads

At that moment Trevor Finch-Bligh and I were engaged in a modest lecture series in Edinburgh — “Crinkles in Time: An Examination of Temporal Dislocations in the Ancient World.” Trevor delivered the photographic evidence; I supplied the anthropological embroidery. We used a magic-lantern projector hired from a firm in George Street, whose operator assured us it had once served to illuminate a Royal Geographical Society soirée.

Arrivals at Tyneholm Park

Lord Thornton and Kamau arrived first, Kamau at the wheel of a hired Rolls-Royce 20 hp limousine, its paintwork the colour of old port. Trevor and I followed an hour later in my uncle Sir Wilfred Whitmore’s Lagonda 2-litre tourer, top down, wind in our hair and the smell of heather thick enough to bottle.

Tyneholm Park appeared suddenly — long drive, cream-coloured gravel, the house a mellow grey pile with oriel windows and a conservatory spilling geraniums. Sir Roger greeted us on the steps, radiant.

“Ruffles! And these must be the celebrated explorers — come in, come in, I’ve chilled the claret!”

The Kennels

Barely had we taken refreshment on the verandah before Ruffles demanded a tour of the kennels.

The kennel yard lay behind a low stone barn built for training pups. A young collie bounded up — black and white, bright-eyed, every inch the heroine of a shepherd’s ballad.

“Her name’s Belle,” said Sir Roger proudly. “Already shows extraordinary promise. Shall we see her work?”

At his whistle Belle dropped into a crouch, circling three ewes in a half-acre paddock. A change of tone, a different pitch, and she slid left, right, forward — the very embodiment of intelligence in motion. When the sheep were neatly penned she trotted straight to Ruffles and leaned against his leg, gazing up adoringly.

“Looks like she’s chosen her master,” Sir Roger laughed. “But beware — genius commands a price.”

Ruffles stroked the dog’s head with the seriousness of a man sealing a treaty.

Dressing for Dinner

That evening Kamau laid out our dinner things with parade-ground precision. He himself wore a white jacket braided red and gold at the cuffs, double-breasted with brass buttons, dark trousers, and his Kikuyu silk turban. Ruffles begged him to sit and dine, but he declined as always, preferring his post beside the sideboard — “where the view of humanity is broadest,” he once explained.

Trevor burst into my room, tie askew and a book in hand. “Look what I found in the guest-room shelves — A History of Medieval Bridges of Scotland! There’s one here, Duffy, on this very estate — the Brig o’ Tyne, sixteenth century at least. I mean to see it at first light. Care to join me?”

“Not I,” I said, tightening my bow tie. “My ambition for the morning runs more to reading The Times in Sir Roger’s conservatory, over Eggs Benedict, oat toast, and Kamau’s incomparable Ethiopian brew.”

Trevor shook his head pityingly at my lack of enterprise and vanished down the corridor.

After-Dinner Diversions

After dinner we gathered in Sir Roger’s library for coffee, liqueur, and cigars. The air was thick with Havana smoke and the faint perfume of furniture polish. Trevor and I had prepared what Ruffles called “an illustrated entertainment on the mysteries of antiquity.” In truth, it was our lecture on the fabled Sator Squares — the Roman palindromes still being discovered on crumbling walls throughout southern France.

I began, as chronicler.

“Trevor discovered a Sator Square embedded on a venerable wall, half hidden beneath a tumble of bougainvillea,” I said. “The famous Roman palindrome — SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS — five words that read the same forward, backward, up, or down. The code of early Christians, some claim; a cosmic crossword, others.”

Trevor beamed and interrupted. “A new find! We’ll dazzle them at the Royal Geographical Society, Duffy. No one has searched or studied Sators for years. It’ll become our specialty.”

“I had to calm him,” I told the company, “offering my whisky flask and recommending deep breathing. He insisted on documenting the thing properly — photographing it from every angle and sketching it in his travel-worn notebook, dimensions carefully noted.”

I let the slide click to the next image. “While he worked, I sat in the shade of an old foundation stone. Presently two ladies appeared, speaking excitedly about their new garden decorations — their new Sator Squares.”

I shifted to French. “‘Bonjour! Where did you find that historic treasure?’ I asked. ‘From the ceramic shop just around the corner,’ they replied.”

“Imagine my difficulty,” I said, “when I looked back to see Trevor, archaeologist’s brush poised above the R of ROTAS, staring in horror.”

Laughter rippled through the room. Even Kamau’s eyes glinted.

“I ambled down the street,” I continued, “and there, sure enough, was a delightful shop selling fine ceramics — specialising in Sator Squares by the dozen.”

Trevor took over with his usual conviction. “Regardless of any shopkeeper’s claims,” he said, “the specimen I found was of Roman manufacture. The fellow merely chose that wall for his sign because it looked respectable. The palindrome itself predates his business by fifteen centuries.”

Cigar smoke drifted through the projector’s beam, giving the photographs of the wall and the bougainvillea a fluttering, ghostly shimmer. Sir Roger leaned forward, the brandy in his glass untouched.

“What my dear friend neglects to mention,” Trevor said grandly, “is that while he was bargaining with the ceramicist, I continued my ascent and found another square in a nearby village — its provenance beyond question.”

“It’s true,” I admitted. “I omitted that heroic detail so I might toast his persistence later.”

I lifted my liqueur glass.

“To starlight on forgotten stones, to maps without edges, and to the splendid uncertainty of finding one’s way.”

The toast drew a murmur of approval. Only Sir Roger did not smile. He regarded us with that level, appraising gaze that can drain a room of warmth.

Sir Roger tapped the bowl of his pipe. “They were a rather disreputable lot, those carnies,” he said. “Travelling show-people with a weather-stained van and an accordion that never quite stayed in tune. They turned up uninvited at our summer fête — the sort of thing the committee pretends not to notice until it’s too late — and by tea-time had wedged themselves between the horticultural tent and the coconut shy.

“They put up a rather garish tent beside the cricket ground, hung with coloured bunting and a placard promising Marvels of Science and Mystery. Inside were the usual trifles — a two-headed duckling in a jar, a mirror that made one appear to hover, and a gentleman who claimed to read the future by examining the soles of one’s shoes. The local matrons queued for an hour to be told they had ‘walked far and would walk farther still.’ It was all splendid nonsense.

“At the same fête,” Sir Roger went on, “they had a tent for the local produce competition — cakes, jams, and so forth. A pair of the fellows got in after hours and rearranged all the labels. The vicar’s wife’s orange marmalade took first prize for Chutney, the blackcurrant jelly was re-entered as Patent Floor Polish, and a rather sorry fruitcake won a ribbon marked Best Exhibit — Any Variety of Root Vegetable.

“The judges, decent souls, did their best to preserve order, but by the time the truth was out the ladies’ committee had collapsed in tears and the band had struck up Rule, Britannia! to drown the noise. It was, I recall, the only moment of real animation that fête ever produced.”

He smiled faintly, tamping his pipe. “So you see, gentlemen, I’ve a small weakness for illusion — provided it declares itself a joke in the end.”

The room went still; only the crackle of the hearth answered him. Ruffles looked momentarily chastened.

Then Kamau stepped forward and replenished Roger’s glass. “In my country,” he said softly, “we say that the past enjoys being remembered — but not being laughed at. Tonight, I think, the past is smiling.”

Roger’s sternness dissolved into a nod. The laughter returned — quiet, civilised, grateful — and the evening, thus rescued, drifted on toward midnight.

Morning in the Conservatory

Morning sunlight poured through the conservatory glass, catching the ferns and the silver coffee pot alike. Kamau, now in his safari khakis and crimson fez, moved soundlessly between the tables.

Sir Roger, buttering toast, asked whether our photographic lecture had been well received in London.

“Mixed reviews,” I said. “Trevor means to redeem our reputation by capturing the Brig o’ Tyne — claims the bridge is haunted by something temporal.”

“Trevor still abed?” asked Ruffles.

“Already gone,” I said. “Off to inspect a medieval bridge — the Brig o’ Tyne.”

Sir Roger looked up. “Across that bridge lives my niece Megyn. Fine girl, Edinburgh Uni, runs her own smallholding. We’ll have her to dinner tonight. But the bridge itself is derelict. Attractive from a distance, yes, but unsafe to cross.”

Kamau was already half-risen. “I’ll bring the Rolls round.”

“I’ll join you,” I added. “Better two of us than one.”

The Herding Exhibition

After breakfast Sir Roger led Lord Thornton to the high pasture for a proper demonstration. From that vantage the River Tyne shone below like a coiled mirror, sheep dotted across the far meadows.

“At a soft command — ‘Fly, go by! Away to me, Belle!’ — the pair raced out in perfect arcs. With each whistle the flock edged nearer, calm as pilgrims.”

The Bridge

Meanwhile Trevor, armed with his Leica and his bridge monograph, had found the Brig o’ Tyne easily enough. The stone arch rose from the water like something dreamt by a mason-poet.

As he knelt to photograph the keystone, a voice drifted down.

“Hallo there.”

He looked up. A young woman stood on the parapet — long dark skirt, green waistcoat, fair hair catching the light. She held a shepherd’s crook with the casual grace of someone born to it.

“Visiting Uncle Roger?” she asked. “I’m Meg.”

He blinked. “Trevor Finch-Bligh. Guilty as charged.”

She smiled. “Admiring our old Brig, then?”

“Indeed. Sixteenth-century workmanship — astonishing.”

“Come to the cottage for tea,” she said simply. And he went.

They talked by the fire about stonework and ancestry until the shadows lengthened. “Are your people Scandinavian?” he asked. She laughed. “A touch of Viking, they say — though the sheep care little.”

When she walked him back to the bridge, he turned once to ask whether he might call again next day — but the parapet was empty. No Meg, no crook, only the echo of water under the arch.

Trevor stood very still. “Oh dear,” he murmured. “A Crinkle.”

Kamau on the Hill

The Rolls climbed through mist and heather. From the crest they saw the old stone arch honey-coloured in the morning light.

Trevor stood on the span, camera poised. “Kamau! Duffy! You won’t believe—”

Kamau sighed. “Too late. He’s met Meg.”

Trevor reached us, breathless. “I just had tea with a shepherdess from another century! Megyn! Golden-haired, radiant — I’m in love!”

Kamau regarded him levelly. “My advice, Mr Finch-Bligh, is to speak of bridges, not of centuries. Sir Roger was not impressed with your presentation last evening, and he’s protective of his niece. Lord Thornton and he have only just renewed friendship, and Lord Thornton is close to acquiring Belle — his blue-ribbon collie. You don’t want to queer that pitch.”

Trevor opened his mouth, still radiant with wonder.

“Gentlemen,” Kamau continued, “for the remainder of the day we remain in the empirical world. Whatever you have seen — or think you’ve seen — must keep till after dinner. Sir Roger has invited Miss Megyn to join us tonight.”

The Rolls purred down the hill, the bridge shrinking behind. Above its single arch a wisp of mist curled upward, twisting like smoke from a projector’s beam.

Part II — The Second Dinner Party

The dining-room shimmered with silver and candlelight. Sir Roger stood to receive his niece; Megyn entered on his arm with composed grace. Across the flowers Trevor met her glance, pressed a finger briefly to his lips, and the unspoken pact was sealed: strangers before witnesses.

Lord Thornton spoke of dog trials and weather; I murmured agreement and applied myself to the soup. Roger presided like a tolerant judge. Conversation meandered from collies to archaeology until Trevor, fatally honest, mentioned “the archaeology of the invisible.” Roger’s fork hovered; I diverted him toward the comparative stubbornness of rams and undergraduates, and calm was restored.

Midway through the soufflé a half-trained collie burst into the room like a small cyclone. Napkins flew; the puppy circled, ignored commands, and settled triumphantly at Megyn’s feet when she whispered “Sit.” Laughter followed, and Roger, robbed of irritation, surrendered a smile.

Coffee and brandy were served in the library, where Kamau awaited beside the lantern projector. “A small dessert of my own devising,” he announced. “Please be so good as to take it here.”

Trevor and Megyn contrived to slip through a side door onto the verandah for air. The night lay cool and moonlit; the Tyne gleamed beyond the trees. Their talk dwindled to silence; faces drew close. Then came Kamau’s discreet cough from the doorway.

“Pardon, sir, madam — dessert is being served in the library. I recommend sampling it while it’s warm.”

They returned like chastened children.

The lights were dimmed; the chairs arranged as for a performance. Kamau stood by the projector. “Before dessert,” he said, “a single slide. Consider it a curiosity.”

The beam struck the screen: the Brig o’ Tyne at dusk. In the foreground stood a woman in flawless medieval dress, her hair bound in a golden snood — unmistakably Megyn. A collective intake of breath; Roger half-rose, knuckles white on the chair arms. Trevor sat frozen. Megyn did not move.

Then the image trembled, flared, and vanished. Kamau drew the slide from the carrier; the glass was blank. “Light,” he murmured, “forgets what men remember.”

Roger’s voice came, cool and final. “If you will excuse me, ladies and gentlemen — it has been a long day.” He left the room.

That night the house sighed itself to sleep. Roger lay awake, staring at the ceiling, replaying the groundsman’s report of the morning — Megyn and the young man in her cottage. He had meant to challenge them, and then that impossible slide… “Trickery,” he whispered, “or something older than trickery?”

One A.M. — A Soft Knocking at the Door

The house slept under a long wind. Somewhere beyond the conservatory glass a branch dragged against the stonework with a sound like a penitent’s whisper.

Then—a knock. Soft, hesitant, but deliberate.

Trevor rose, barefoot on the carpet, and opened the door a cautious inch.

There stood Megyn, a candle trembling in its pewter holder, the light fluttering over her hair so that it seemed spun from the same flame. She was in her nightdress, barefoot, the hem brushing the floor, her expression somewhere between apology and conspiracy.

“I’m sorry,” she said softly. “The wind’s pushing the branches against my window. It sounds as though someone’s trying to get in.”

Trevor glanced down the corridor—no one. “Come in, quickly.”

He caught her forearm lightly, the way one might steady a dancer at the start of a reel, and drew her inside. The door closed with an almost civilised click.

For a moment neither spoke. The candlelight flickered over the brass bedstead, over the books scattered on the chair, over her face half-turned toward the fire.

“Well,” Trevor said at last, “I daresay we can outwit a few branches.”

Megyn gave a nervous laugh, then met his gaze—an instant too long for mere reassurance.

Outside, the wind muttered its complaint along the eaves, but inside, all was conspiratorial stillness.

Two A.M. — The Bleating

From the fields came a cry, thin and lost. Doors opened; candles flared. Roger, already wrestling with trousers under his nightshirt, hurried past my door. In the next room Megyn stirred.

“What is it, darling?” she murmured.

Trevor was already up. “Nothing. Go back to sleep.” He grabbed a lantern and ran.

Mist clung to the meadow; the Tyne murmured below. A ewe stood trapped, roots knotted round her leg, a lamb wailing beside her. Roger was in the mud, grappling with both. “Hold still, girl,” he grunted — and slipped.

“Hold on, sir!” Trevor splashed down, caught him under the arms, and heaved. The lamb broke free; both men slid towards deeper water.

“Rope,” said a calm voice.

Kamau appeared at the bank, coiled rope in hand. Three motions — and man, ewe, and lamb were on solid ground again.

Roger looked from Kamau to Trevor. “Well,” he said at last, very low, “it appears your Crinkles include miracles.”

“Hardly that, sir,” said Trevor, wiping his face and grinning like a boy. “Only a bridge between inconveniences.”

First Light

At first light the house told itself the story in improved versions. Towels were brought, and blankets, and a brandy whose sincerity could not be doubted. Lord Thornton congratulated everybody impartially, and Belle, hearing her name in the commotion, presented herself as if the whole affair had been arranged for her benefit. The puppy, who had no part in it whatsoever, accepted credit with his usual grace.

Sir Roger, dry and proper once more, held out his hand to Trevor. “Mr Finch-Bligh,” he said, “a man who pulls another out of the Tyne may be permitted an interest in bridges.” He hesitated, then added in a tone that might almost have been amusement, “Even bridges that misbehave.”

Kamau poured coffee into the silence that followed. “Bridges, sir, prefer to be crossed twice,” he observed. “Once in doubt, and once in understanding.”

Megyn looked over her cup at Trevor, and somewhere behind the formality I thought I heard the faintest bell struck on a day that had not yet begun.

Thus ended the Second Dinner Party at Tyneholm Park; and if the Brig o’ Tyne keeps its own counsel about what it saw, I, for one, will not insist upon cross-examination.

—Duffy Whitmore