La Maline (The Sly Girl)

• Unveiling Rimbaud’s Moral Boundaries •

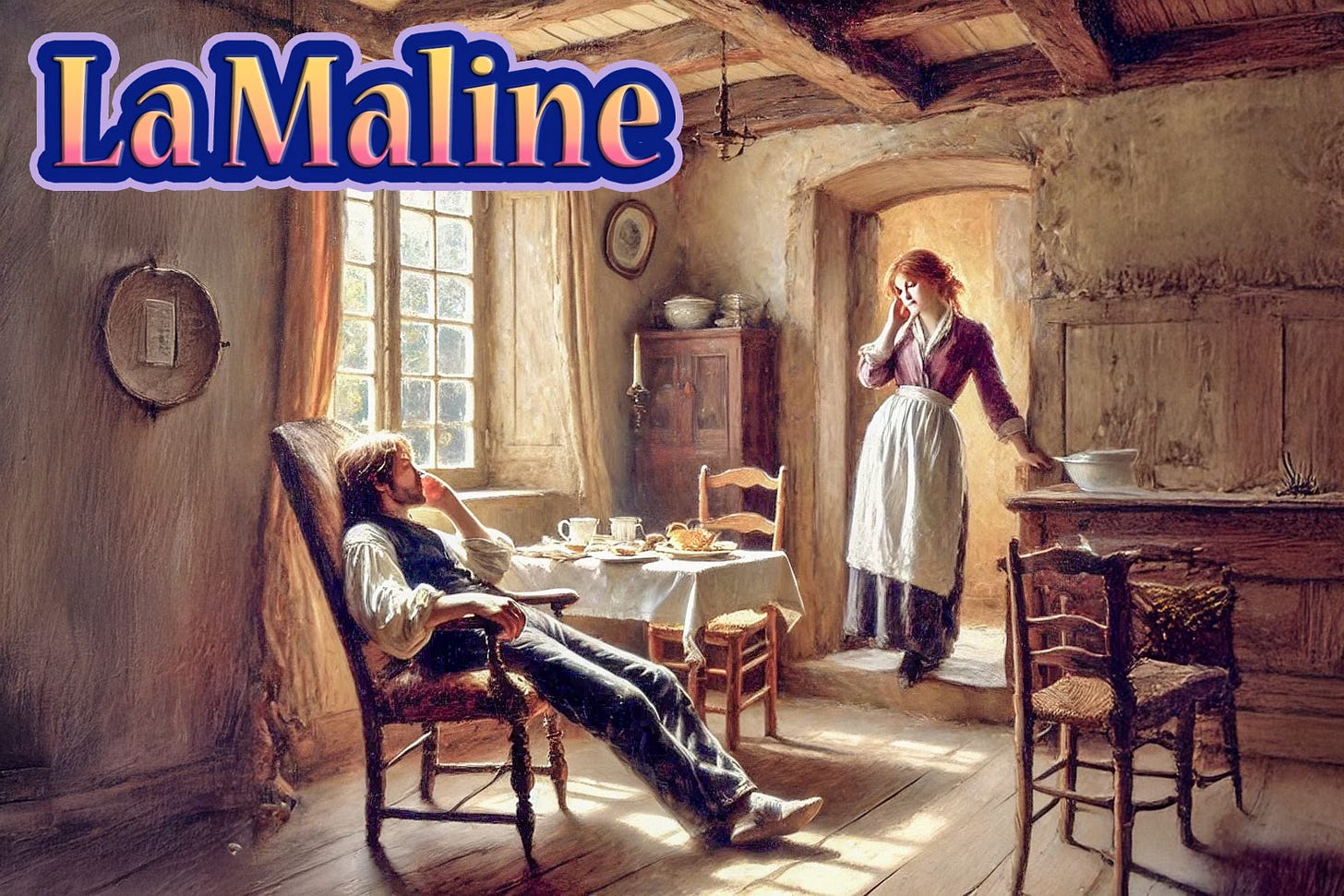

La maline (For those who prefer the original French) Dans la salle à manger brune, que parfumait Une odeur de vernis et de fruits, à mon aise Je ramassais un plat de je ne sais quel met Belge, et je m’épatais dans mon immense chaise. En mangeant, j’écoutais l’horloge, — heureux et coi. La cuisine s’ouvrit avec une bouffée —Et la servante vint, je ne sais pas pourquoi, Fichu moitié défait, malinement coiffée Et, tout en promenant son petit doigt tremblant Sur sa joue, un velours de pêche rose et blanc, En faisant, de sa lèvre enfantine, une moue, Elle arrangeait les plats, près de moi, pour m’aiser; —Puis, comme ça, bien sûr, pour avoir un baiser, — Tout bas: “Sens donc: j’ai pris une froid sur la joue ... —Arthur Rimbaud The Sly Girl (Wallace Fowlie Translation) In the brown dining room, perfumed With an odor of varnish and fruit, leisurely I gathered up some Belgian dish Or other, and spread out in my huge chair. While I ate, I listened to the clock—happy and quiet. The kitchen door opened with a gust —And a servant girl came, I don’t know why, Her neckerchief loose , her hair coyly dressed And as she passed her small trembling finger Over her cheek, a pink and white peach velvet skin And pouted with her childish mouth, She arranged the plates, near me, to put me at ease; —Then, just like that—to get a kiss, naturally— Said softly: “Feel there: I’ve caught a cold on my cheek. . .”

THE CONCEPT:

A short film concept that expresses my view of “La Maline” as a representation of Rimbaud’s restraint.

For fun, I take us to Oxford to the rooms of none other than Evelyn Waugh (as an Oxford don), expressing his view of young Rimbaud as evidenced in the incident that occurred in that humble dining area, somewhere in Belgium…

Imagine a short film that encapsulates Arthur Rimbaud’s poem “La Maline” as a testament to the poet’s restraint. Set within the distinguished rooms of Evelyn Waugh at Oxford University, the film portrays Waugh, embodying the role of an Oxford don, delivering a compelling lecture to his students. He delves into Rimbaud’s youthful encounter in a modest Belgian dining room, interpreting it as a significant display of the poet’s self-control.

The narrative unfolds as Waugh vividly recounts the scene from “La Maline,” highlighting the subtle dynamics between the adolescent Rimbaud and the coquettish maid. Through Waugh’s articulate analysis, the film explores themes of temptation, innocence, and the moral fortitude required to resist impropriety. The setting of Waugh’s Oxford quarters, adorned with literary artifacts and steeped in academic ambiance, serves as a poignant backdrop that bridges the Victorian era of Rimbaud with Waugh’s early 20th-century milieu.

This cinematic piece not only offers a deep literary analysis but also pays homage to the intellectual traditions of Oxford. It underscores the timeless relevance of Rimbaud’s work and the enduring importance of ethical integrity, as illuminated through Waugh’s scholarly perspective…

FADE IN:

INT. OXFORD UNIVERSITY - DON’S STUDY - EVENING

A warmly lit room lined with towering bookshelves. A fire crackles in the hearth. EVELYN WAUGH, a distinguished man in his mid-40s with a sharp gaze and a hint of mischief, stands before a small group of STUDENTS seated attentively. He holds a well-worn copy of Rimbaud’s works.

WAUGH

(holding up the book)

Gentlemen, tonight we delve into Arthur Rimbaud’s “La Maline.” Let’s begin with the opening lines.

He reads from the book.

“Dans la salle à manger brune, que parfumait

Une odeur de vernis et de fruits…”

Ah yes—the brown dining room, Rimbaud says, and how vividly this scene begins, with that curious mixture of fruit and varnish hanging in the air. “Brown,” you see, not merely as a color but a whole atmosphere. A lacquered somberness. One thinks of middle-class provincial Belgium, a place that never quite escapes the smell of overripe pears and mahogany polish.

“à mon aise / Je ramassais un plat de je ne sais quel met Belge…”

“At my ease,” he says, “I helped myself to—what was it?—some Belgian dish I can’t quite name.” Here we have Rimbaud with that particular Gallic disdain for foreign cuisine. He’s lounging in an oversized chair—“immense,” he calls it—and very pleased with himself, though that smugness will not last.

“En mangeant, j’écoutais l’horloge,—heureux et coi.”

He eats. He listens to the ticking of the clock. He is happy, he says—and quiet. Now that, gentlemen, is important. He is still in repose. The world is orderly.

“La cuisine s’ouvrit avec une bouffée…”

But then! The kitchen opens. A puff of air, perhaps of steam. And with it—

“Et la servante vint, je ne sais pas pourquoi…”

“The maid entered—for no particular reason,” he claims. Oh, but of course she had a reason. This is not merely prose. This is theatre. And she knew her part. Observe:

“Fichu moitié défait, malinement coiffée…”

Her handkerchief—half undone. Her hair—carefully disordered. Not slovenly, mind you. No, no. Mischievously arranged. This is artifice. A child’s attempt at seduction, rehearsed in mirrors.

Now, I would ask you to pause here. Because this is where the popular notion of Rimbaud as the fevered libertine begins to dissolve—at least for me.

Rimbaud is amused, yes. But he is also squeamish. He doesn’t move. He doesn’t speak. He watches.

“Et, tout en promenant son petit doigt tremblant / Sur sa joue…”

She trails a little trembling finger down her cheek. A velvet of peach and milk—so he says. But again, note the distance. He’s observing her in the same way he might observe a bird with painted wings strutting through a parlour.

“En faisant, de sa lèvre enfantine, une moue…”

She pouts—a child’s pout. Again, he calls her lips enfantine. Childish. He is not titillated, gentlemen. He is trapped. And more than that—he is discomfited.

“Elle arrangeait les plats, près de moi, m’aiser…”

She fiddles with the dishes, hovering a little too close. He doesn’t say a word. He doesn’t touch her. He lets the scene play out, and he watches it with the eyes not of a predator—but of a poet with a sense of moral boundary.

Now this line:

“Puis, comme ça—bien sûr, pour avoir braiser,— / Tout bas: ‘Sens donc: j’ai pris une froid sur la joue…’”

“Then, just like that,” he says, “as if—of course—to have me look closer, she murmurs: ‘Feel this—I’ve caught a chill on my cheek…’”

This is not a seduction. It is mimicry. A performance drawn from some overheard gossip or play. And Rimbaud—contrary to his reputation—does not oblige. He does not touch her cheek. He ends the poem here. With her line. With her pretense of suffering. And in doing so, he gives us something more complex than mere appetite.

He gives us restraint. He gives us discomfort. And perhaps—just perhaps—a trace of pity.

Waugh leans back now, lips pursed, fingers steepled. A log shifts in the grate. Outside, Christ Church bells mark the hour—but he is not yet finished…

So. There you have it. A poem that many would lazily file under adolescent decadence. A scribble from the boy-genius drunk on sensation, dashing off verses between absinthe and bad company. But that reading, I submit, is not only vulgar—it is stupid.

This is not a libertine’s fantasy. It is a young man—still very much a boy himself—meeting the performance of femininity and feeling not desire, but squeamishness. Not temptation, but unease. He has stepped into the realm of theatre—domestic theatre, no less—and finds himself cornered by the world’s falsest force: a child pretending to be a woman.

What does he do?

Nothing.

He watches. He records. And most importantly—he refrains.

Now, if this were Baudelaire—or, God forbid, Verlaine—we might be reading about the lace falling from her shoulders, or the “pale ecstasy” of her skin. But this is Rimbaud. And say what you like about the hell he walked into later—at this moment, in this brown dining room, he showed a kind of moral fastidiousness that was almost English.

Yes, English.

One of your lot—not the poets, mind—but the public-school boys. Those solemn forms of restraint. That horror of appearing to enjoy oneself in the wrong company.

So remember that, gentlemen—and ladies, if any are still listening—when next you hear someone droning on about the debauched Rimbaud. Tell them to read La Maline again. Carefully. And to note that sometimes the clearest measure of a man’s character lies not in what he desires—but in what he refuses.

Now then—who’s for a drink?

—Duffy Whitmore

This is a lovely tour of beautiful literature. Deeply insightful and a pleasure to read (slowly in French) and deeply enjoy.