Roi d’Élégance

• A Duffy Whitmore Adventure •

Roi d’Élégance

A Duffy Whitmore Adventure

Epistolary Prelude

12 May ’35

Somewhere on the bloody Congo

Dear Trev,

I trust this note finds you hale and in possession of all necessary faculties. Duffy’s last wire mentioned—rather too casually, I thought—that your Olivia may soon descend upon Happy Valley. Brace yourself. That valley hasn’t seen such a tempest since the gin shortage of ’29.

As for myself, I fear I may miss Ruffles’ safari, though not for lack of enthusiasm. I’ve gone and stranded myself in the Congo, of all places—on a photo assignment that’s become more Heart of Darkness than Picture Post. I’m drifting upriver in pursuit of a legend—Kurtz, or someone pretending to be—but I fear I’ve found someone far more dangerous.

Enclosed, you’ll find a portrait of yours truly, taken by one of my porters. I attempted a Burtonian jawline, with debatable success. There’s a mosquito bite on my temple which gives the impression of a thoughtful furrow, so I’ve decided to claim it as such.

I’m currently perched in a stilted hut with a ladder for access (or escape), surrounded by mosquito netting, the air thick as molasses, and the nights broken by the sort of noises that suggest Nature regrets being colonised.

But yesterday—good Lord, Trev—yesterday I saw her.

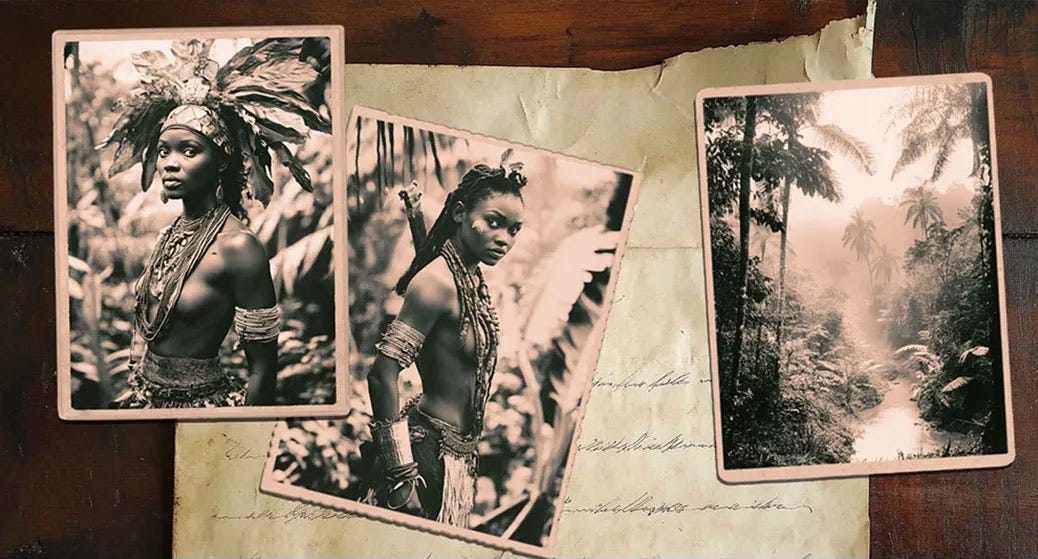

She emerged from the forest like an apparition—no, that’s too pale a word. A vision, wild and resplendent, draped in striped cloth, her neck heavy with charms that caught the light as she moved. There was brass at her knees, fire on her cheek, and something about her bearing—so upright, so sovereign—that made me think she came from a lineage of queens. She was the Congo itself, incarnate and unbothered by European notions of modesty or mortality.

I took twelve shots from the deck of the steamer as we passed—each one more unreal than the last. I must find her again.

I’m shooting black and white negatives—more practical, given the vagaries of development in Matadi—and I’m travelling with two Leicas now: one with a 50mm mounted, for portraiture, and one with a 35mm mounted, for the wider drama of it all. If the prints do her justice, I’ll enclose a few in my next letter. Ruffles may want to see them. In fact, I was thinking—do whisper this in his ear if the mood strikes him—that a proper expedition might be in order. A steamer of our own. Field tents. G&Ts at dusk. And the chance to document what no man has yet dared photograph without being speared.

You know what I’m thinking, don’t you? The Geographic Society. An evening lecture. Slides. Applause. A standing ovation, perhaps, followed by supper at the Savoy. I’ll need to be more Odysseus than Ulysses, clever but not craven. And should she appear again—I’d not have turned her away like that fellow in Conrad’s tale. I’d have offered her tea, taken the risk, and gone down with the ship, camera in hand.

Ever your devoted savage in the bush,

Rory

15 May ’35

Happy Valley

My dear Duffy,

All of us here in Happy Valley await word of your triumphs, introducing the Crinkle in Time to a public as dimly aware of its existence as they are of a decent sherry. One hopes your London audience can keep up. No doubt you are dazzling them—though I suspect the dons only tolerate your heresies because you wear a tie.

I trust you’ve found a spare hour to drift into the National Portrait Gallery and cast a glance at my modest offering:

“Lord Thornton Beside the Dancing Princesses Bas-Relief, Bombay, 1935”

Photographer: Trevor Finch-Bligh

Black-and-white, naturally. Colour would have been vulgar.

I received a letter—typewritten, no less—from Rory, presently meandering up some fetid tributary in the Congo. He is, it seems, in pursuit of a jungle goddess who appeared to him on a riverbank. Whether this vision was native, mythic, or medicinal in nature remains unclear. I enclose his account for your edification and to spare myself the burden of explanation; the whole thing is wonderfully Rory. He sounds smitten—again. I admit, I wouldn’t mind joining him: for the story, for the snaps, and possibly for the jungle goddess. There’s surely still a market for that sort of thing—though one must now label it “contemporary ethnographic portraiture” to avoid cancellation.

That said, the photograph enclosed with his letter—snapped by a porter and probably posed with Burtonian self-regard—betrays something else entirely. He looks stricken. As though the jungle heat has failed to sweat out the sting of Khush’s letters—the ones that greeted us like silent telegrams of doom the moment we stepped off the Eurycleia in Bombay. Not one of us said anything aloud, of course; we simply watched him read them with the grim expression of a man deciphering hieroglyphs that mean “abandon all hope.”

I did manage to unearth a photograph of Rory and Khush—perhaps the only one of them together. I took it on that little day trip we made, up the coast from Bombay. You may remember: the Homeric furniture, the sea like pewter, and Kamau’s unforgettable crab curry. She’s smiling, but it’s the kind of smile a clever woman offers a man she’s about to escape from. We now know she fled to Jaipur the next morning, which suggests the smile was rehearsed.

Think about joining me for a jaunt out to the Congo. Rory might benefit from a reminder of civilised company—and you might locate another Crinkle. There must be dozens, wedged in the vines and heat, just waiting for the right man to find them.

Yours in mischief and mildew,

Trevor

(Somewhere between civilisation and the great, green unknown)

Dear Trev,

You’ll forgive the stationery. The concierge—an exiled Walloon with a cleft palate and a flair for gin rations—offered me only this mourning-grade writing paper or an old shipping manifest from a rubber concern. I chose the less ominous of the two.

I’ve just arrived in Matadi, or as the French spell it: mildew. My boots, once polished to a West End gleam, are now the colour and consistency of boiled okra. The jungle exacts its toll with cruel and deliberate enthusiasm.

Enclosed you’ll find two photographs of what I initially believed to be the same jungle priestess. Both taken upriver under frightful conditions—humidity like a Turkish bath run by sadists and mosquitos with French names. One shot was developed in situ (a miracle involving a Boy Scout torch, powdered hypo, and a bedsheet) and the other, here in Matadi, in the converted bath of a fellow Brit named Fanshawe who claims to be mapping the Congo but is really compiling an annotated memoir of his lovers. He brews an excellent quinine cocktail and has a suitcase full of Ilford stock, so I forgive him his eccentricities.

Now—this is the most remarkable bit—I’m quite sure they are not the same woman. Look at the cheekbones in Plate A, the height-to-arm ratio in Plate B. Entirely different priestesses. This isn’t a singular goddess—it’s an order. A veritable convent of wild, elegant, poised and alarmingly capable priestesses.

I am now convinced I’ve stumbled upon a matriarchal cult or possibly the long-lost daughters of Isis, relocated and rebranded for the tropics. They wield spears with balletic grace and seem entirely uninterested in trousers or Christian values.

I leave tomorrow on a small steamer named Victoire (optimistically titled), hoping to retrace my path upriver and locate their encampment. I may not return. Or I may return with the key to a forgotten ethnographic epoch—and possibly a few phone numbers written in charcoal on bark.

Fanshawe insists I submit the prints to the Royal Geographical Society, who might just mistake me for a serious man of letters. Imagine! Rory Maher, FRGS. My mother always said I’d amount to nothing. If only she’d known it would be a tribe of savage, barefoot priestesses who gave me purpose.

I’ll write again—if I haven’t been turned into a fertility idol or eaten by one of Fanshawe’s ex-wives.

Yours in sweat and sepia,

Rory

3 June ’35

My dear Duffy,

Your most recent dispatch—posted, I see, from a Woolworth’s near Charing Cross—has just arrived, tied with string and trailing the scent of coal smoke and boiled ham. It came via steamer to Mombasa, was forwarded on the Lunatic Line, sat inexplicably in Kisumu for a week (no one can explain why), and finally reached Nairobi stuffed into the hunting boot of a Punjabi courier who swears he saw Lady Delamere wrestling a parrot at the post office. All quite routine.

But I write in earnest.

This morning, over an aggressively colonial breakfast (kippers and quinine, mostly), Lord Thornton and I read Rory’s latest letter—the one posted from Matadi, full of priestesses and darkroom improvisation and Fanshawe’s scandalous bathwater.

Duffy, I fear the man has gone completely barking.

Heatstroke, moon-madness, or the smouldering gaze of an ethnographically ambiguous priestess—take your pick—but the Rory we knew, the one who once argued with a museum guard over the erotic symbolism of a Cycladic fish hook, is now preparing to vanish upriver, into territory last charted by botanists with sketchbooks and very little follow-through.

We must act.

Lord Thornton agrees, reluctantly—it took two tumblers of Dubonnet to get him onboard—but agrees nonetheless: we must mount an expedition. I’ll secure passage from Mombasa by way of Léopoldville and from there press onward by steamer, lighter, and if need be, foot. I’ll bring the Leica (two, in fact), spare socks, a case of flash powder, and a khaki shirt with enough pockets to seduce a postmaster.

Not only do I intend to find Rory and retrieve him, but if his priestesses truly exist (and if they’ll consent to posing), I shall photograph them with all the delicacy and reverence of a Harrow man attending a debutante’s ball. This could be the portfolio of my career—or the end of it.

Chuck whatever lectures you’re giving on the Crinkle, or at least wrap up the ones in Bloomsbury. I may need your linguistic gifts and your abysmal sense of direction, both of which served us reasonably well in Smyrna.

Telegram to follow.

Yours ever,

Trevor

(Finch-Bligh, if you’re publishing this in your diary)

P.S. If Rory has been crowned tribal consort to a pagan matriarchy, I expect a formal invitation to the ceremony.

Prologue

London, June 1935 — The Central Library, Russell Square

It is raining in the dependable English way, the kind of drizzle that glances off bowler hats and slicks the brass doorknobs of Piccadilly. Here, in the central reading room, I sit beneath a row of green glass lamps, the sort that cast a gentle, collegiate light upon maps of dubious accuracy. Outside, the city sulks under a pewter sky. But inside—within these stone walls lined with encyclopaedias and dangerous ideas—I prepare for the jungle.

Before me lie several picture books of the Congo basin—most of them authored by Belgians with a troubling moustaches. I’ve been leafing through them with a scholar’s disinterest and a traveller’s rising dread. The illustrations include a number of stylised hippos, an enthusiastic rendering of a mangrove thicket, and a diagram—improbably cheerful—depicting the life cycle of the tsetse fly.

Why, you ask?

Because Rory has gone missing. Not vanished precisely—he continues to write, intermittently, with all the florid courage of a man who doesn’t yet know he’s in peril. But his letters suggest an encroaching madness: something about a “jungle goddess,” an “order of priestesses,” and “balletic spears.”

Add to that the involvement of a man named Fanshawe (an alleged cartographer and confirmed lothario), and it becomes clear: Rory needs rescuing. Or, at the very least, chaperoning.

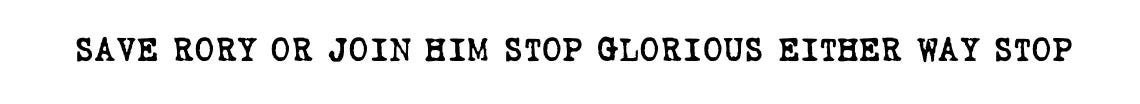

Trevor has cabled me from Happy Valley with a plan involving Lord Thornton, a steamer of suspicious provenance, and a great many field tents. The telegram, now tucked neatly into the cover of my Baedeker’s, read simply:

Well then. Let the expedition commence.

Chapter I:

The Hotel Stanley, Matadi, Belgian Congo

It was precisely the sort of hotel one expects to find in Matadi: a faded colonial mirage with slow fans, quick gin, and bathwater the colour of weak tea. We rendezvoused in the upstairs parlour, where wicker chairs wheezed under the weight of expatriates and geckos hunted openly along the rafters. Outside, the jungle pressed in like a pick-pocket .

Trevor arrived first, looking tan and crisply starched, though one of his Leicas had already acquired a tropical mildew. He’d brought a stack of Rory’s letters, each one madder than the last. Kamau followed, carrying two crates of photographic equipment, a collapsible gramophone, and an expression that suggested he’d rather be anywhere else—including Jaipur, Smyrna, or the inside of a lion.

Lord Thornton descended last, dressed as if embarking on a pheasant shoot in Surrey.

Chapter II:

A Short Drive Through Hell (with Stops)

The lorry was British Army surplus, left behind by someone with poor taste in timing and poorer taste in maintenance. It arrived at the Hotel Stanley precisely two hours late, painted an indeterminate shade of colonial despair, and driven by a youth named Lucien who claimed to be half-Walloon, half-Cabindan, and wholly unfit for the job.

Trevor, ever optimistic, supervised the loading of the crates himself: photographic gear, canvas tents, tins of tongue, mosquito netting, a collapsible writing desk, several bottles of quinine-and-something, and Kamau’s private collection of books—which included Pliny the Elder and a banned French edition of The Decameron. Lord Thornton insisted on supervising the packing of the Dubonnet personally, muttering that “matters of morale mustn’t be left to porters or chance.”

Lucien, meanwhile, flirted shamelessly with the hotel’s proprietress, a Belgian widow of impossible sternness and impossible waistlines, whose cats outnumbered the guests three to one.

By the time we finally set off, it was nearly noon and already hotter than a missionary’s brow in a brothel.

We’d only gone a few miles beyond the outskirts of Matadi—where the jungle begins to reassert its authority—when we struck our first obstacle: a tree, freshly hacked down and left sprawled across the road like a barricade. Kamau knelt to inspect the clean axe-marks, then rose with a look that said, plainly enough: this was no act of God.

Lord Thornton grumbled, Trevor photographed it, and I sat on a stump writing a haiku about futility:

Jungle in revolt—

lorry sulks beside the road,

mosquitoes plot war.

Lucien swore, reversed, and took what he referred to as a “shortcut.”

It wasn’t.

Within ten minutes, we were axle-deep in what may once have been a road but was now a slough of red Congolese mud. A goat watched us from a distance with the gaze of an ancient judge. Trevor’s crates shifted violently; something shattered—possibly the gin, possibly a light meter.

Kamau calmly stepped out, rolled up his sleeves, and began to dig us out with a camp kettle. Lord Thornton attempted to direct the process from a shaded copse. I, meanwhile, helped by documenting the scene in case it became a formal inquiry.

It was nearly dusk when we reached the riverside dock.

The steamer loomed in silhouette, its upper deck lights aglow, reflecting on the black water like lanterns from a half-remembered dream. An old African man was seated at the dock with a fishing rod and a face like cracked leather. When we passed, he looked up and said, in English as fine as Eton’s: “That boat has waited a long time.”

No one asked what he meant. Some things are best left ambiguous.

Chapter III:

The Boat That Waited

It was not, as the official papers would later claim, an acquisition so much as a disentanglement—a gentleman’s rescue mission from the clutches of bad debt and worse company.

Two weeks prior, Lord Thornton—Ruffles to his friends, and “that blasted Englishman” to everyone else in the Léopoldville club—had entered a dim and unreliable bar known euphemistically as Le Théâtre des Possibles. Its clientele was a mixture of shipping agents, diamond runners, and colonial widows with flexible standards. The décor was mostly smoke and regret. A ceiling fan rotated above the table like a bored vulture.

Ruffles had arrived uninvited, which was his preferred method. He wore white linen, a faint scent of bay rum, and the air of a man with access to Swiss accounts and unspeakable anecdotes about ambassadors’ daughters.

He ordered a Dubonnet. The bartender, a former Portuguese opera singer named Marcellina, poured it with the sort of intimate precision that implied she had once been married to a French admiral and now considered the British aristocracy a spiritual upgrade.

At the back table: a game in progress. The dealer was a Danish ivory man with nicotine fingers and an eye that didn’t quite look where it should. The players included a Belgian colonial judge (recently suspended), a Brazilian arms trader pretending to be Dutch, and one Monsieur Delapierre—a creature of unknown origin and disputed nationality who claimed to be the rightful owner of a steamship moored, with some ambiguity, just downriver.

The ship’s name—Roi d’…elge—had long ago faded beneath layers of lichen and bureaucratic neglect. It had been a floating casino, a missionary transport, a private pleasure barge for a Zanzibari prince, and once, if rumour held, a quarantine vessel for yellow fever patients. Now it lay tied to a dock, waiting for someone foolish or brilliant enough to claim it.

Lord Thornton was both.

He sat, placed his cigarette case on the table as collateral, and joined the game.

No one remembers precisely what happened next—least of all Delapierre, who was two Negronis ahead of his own luck. But by morning, Ruffles was the proud owner of a steamer, a Flemish hunting dog and a half-written opera libretto about cashew smugglers. He accepted all three with his usual calm. The dog, he renamed Fitz. The opera, he abandoned in a drawer. But the boat—the boat he kept.

When the Chaps later asked how he’d secured it, Ruffles simply said:

“Always gamble with men who sweat through their collars. They always overplay their hand.”

He never mentioned that the boat’s deck was still faintly haunted by the sound of roulette wheels. Or that Marcellina had whispered, as he left the bar, “It will take you somewhere you do not expect to go.”

But that, of course, is what boats are for.

Here was the steamer Ruffles had won at the poker table—he referred to it as “an optimistically floatable vessel”–– tied at the riverside—Ruffles had supervised its provisioning with the brisk despair of a man who once lost his luggage and his valet on the same afternoon in Alexandria.

“She’ll do,” he muttered, as we approached the boat.

The exterior was, let us say, well-travelled: rust spots like liver stains, a name partly rubbed away—Roi…d…elge—and a gangplank that required a certain leap of faith.

But once aboard, the interior surprised us all. There was a proper bar with glassware, a walnut-paneled dining salon, and a faint scent of lavender that no one could explain.

I dropped my haversack in a cabin fitted with a mosquito net and a copy of Punch from 1926.

Trevor, inspecting the hull, said quietly, “I don’t suppose anyone’s bothered to look up what happened to the original Roi d’Belgique, have they?”

No one answered. Kamau lit a cigarette. Lord Thornton adjusted his cufflink.

“I say we don’t ask,” I said, and was immediately appointed morale officer.

Chapter IV:

The Ascent

The jungle, I am convinced, prefers not to be noticed. At first light, it recedes into fog with such theatrical subtlety that one might think it embarrassed to be caught so unkempt. But the river—she puts on a show. And it was through this rising curtain of grey that we began our ascent.

We had been drifting for hours by the time I rose, having found little success sleeping in a bunk clearly designed for a smaller, more optimistic man.

The Roi d’Élégance made her sluggish way upriver—half paddleboat, half gentlemen’s club—partially restored, eternally undermanned, and wholly unsuited for anything beyond an ornamental lake. Still, her polished brass fittings gave one a sense of ceremonial grandeur, even as the engine wheezed like a dowager in damp linen.

I emerged onto the quarterdeck expecting solitude and a pot of weak tea. Instead, I found Trevor Finch-Blythe standing at the stern, stock-still, clutching a mug of Kamau’s Abyssinian coffee —tilted just enough for it to spill, unnoticed, onto the deck. He looked paler than usual, which is saying something for a man who goes translucent in anything stronger than candlelight.

At the rail, and only barely visible through the low, churning fog, stood a figure. Human in outline, but distinctly other in presence. Barefoot, motionless. Adorned in ash, copper, and silence. He—or it—stared not at the boat, but at the river itself, as if attending to some conversation that had begun centuries earlier.

And then, he vanished.

Not theatrically.

Not with a flourish.

Simply… gone.

Trevor inhaled sharply. Kamau appeared beside him as if he had been standing there all along. He was, as ever, composed. “He is a sentinel,” Kamau said calmly. “A warning. I have understood the message. I will inform Bwana when he awakes.”

Trevor blinked. “You mean you understood it?”

Kamau sipped his coffee. “Correct.”

“And what was the message?”

Kamau gestured to the fog. “That we are being watched. Closely. That we are not the first, nor the last.”

Trevor looked as if he might require a chair, or a small church. Fortunately, Fitz—Lord Thornton’s imperturbable dog—ambled out and sat beside him, thudding to the deck with canine finality. He stared out into the mist, gave a single, aristocratic yawn, and leaned his warm weight against Trevor’s trouser leg. It helped.

By mid-morning, the fog had lifted, leaving behind only the lingering sense that something ancient had passed us by.

Kamau summoned the rest of us to the quarterdeck for what he dubbed, with professorial solemnity, The School of Jungle Etiquette.

“Gentlemen,” he began, pointer in one hand and coffee in the other, “what we know about these women is minimal. They may be priestesses—possibly of an shamanic class, if one subscribes to current research. Rory calls them goddesses, and surprisingly, he might be right.”

He paused here. Not for dramatic effect, but because Lord Thornton had arrived in a cloud of aftershave and Colonial Office scepticism, nursing a tall gin fizz and wearing the sort of Panama hat that would not survive a breeze.

Kamau continued.

“Simply put—as the Americans say—they’re drop-dead gorgeous. That’s where the trouble starts.”

“Not even a polite wave?” Trevor asked.

“Not even a cough,” said Kamau. “Do not address them. Do not offer them tea, money, cigarettes, or compliments on their necklaces. Under no circumstances allow them to come aboard.”

“They might know where Rory is,” Trevor countered.

“They know more than Rory’s whereabouts,” Kamau replied. “And would prefer to keep it that way.”

“What if she’s wearing an Eton tie?” I asked, sincerely.

“Then you definitely don’t speak to her,” Kamau said without hesitation.

Lord Thornton took a thoughtful sip of his gin. “I say, what if one of them hails us with information?”

“She won’t,” said Kamau. “If you hear her call your name, it is not her voice you’re hearing. It’s your own worst idea in disguise.”

On a section of cardboard displayed on Trevor’s French easel, Kamau had written, in bold block letters, a list of further rules:

Do not pick up carved items left on the riverbank.

Do not enter huts, no matter how artfully thatched.

If offered a gourd to drink from, decline.

If you hear drumming, it is not an invitation.

If Lord Thornton insists on waving, pretend to not know him.

He laid his pointer down, closed his leather-bound manual of field observations and tucked it under one arm.

“Your homework for this afternoon: reread Circe’s instructions to Odysseus regarding the Sirens. That is what we are dealing with here.”

Trevor raised a hand. “Do you mean metaphorically?”

Kamau looked at him. “No.”

And with that, the day grew hotter, the insects louder, and the foliage thicker. But the boat pressed on, elegant in her decrepitude, trailing a pale wake through water that looked like polished jade. The jungle, in turn, observed us without expression.

Somewhere upriver, Rory waited.

Or perhaps he didn’t.

We had begun the ascent.

And the rules, it seemed, were shifting.

Chapter V:

The Siren on the Shore

Those who have not cruised upriver on the Roi d’Élégante cannot imagine the peculiar sense of suspended time she induces. For days the voyage resembled a particularly pleasant house party, albeit one adrift in the steaming wilderness. Trevor, wearing a pith helmet cocked at a rakish angle and a shirt he claimed once belonged to Max Beerbohm, spent his hours beneath the rear deck’s striped canopy, coaxing viridescent washes of riverside foliage in sap green and burnt umber. He painted with the dreamy absorption of a man already imagining his work on display at the Royal Academy—or, failing that, hung just above the cigar cabinet at The White Stag, where it might be admired between rubbers of bridge and slightly scandalous anecdotes.

Duffy, meanwhile, was rarely seen without a notebook and a pair of pince-nez that he had taken to wearing solely to lend gravitas. He claimed to be preparing an address for the Royal Geographical Society and some London-based women’s clubs, where the questions tended to be sharper, and far less deferential, than anything he’d encountered at the RGS.

Lord Thornton, the only one of the party to wake before sunrise, could be seen each morning performing deep knee-bends and one-armed pushups with heroic concentration on the forward deck. This display—accompanied by grunts and the distant aroma of Kamau’s beloved Abisynian roast—was not to be witnessed without a twinge of patriotic admiration.

Between calisthenics and a second breakfast, Ruffles continued polishing the sixth volume of his memoirs, tentatively titled, “Crisis at Cricklewood: A Memoir in Twelve Improvised Chapters.” Several pages were devoted to the incident at the Cheltenham Literary Festival, which he swore never to speak of aloud again.

Fitz, our adopted mascot onboard and de facto morale officer, spent most afternoons patrolling the perimeter of the boat in a state of quiet vigilance. On several occasions he paused near the galley, sniffed the air with philosophical doubt, and resumed his circuit, tail stiff with unresolved suspicions.

Kamau, meanwhile, had become something of a fixture in the wheelhouse, quietly apprenticing under the Roi d’Élégante’s Skipper—a leathery, taciturn fellow known only as Mudge, who had been engaged at the last minute in Léopoldville and claimed, with neither pride nor humour, to have “seen farther upriver than Conrad dared write.” Mudge had a peculiar fondness for clove cigarettes, which he rolled with a dexterity that suggested either a criminal past or clerical training.

It was under this illusion of safety—this mirage of a civilised cruise afloat in the savage interior–– when the spell was broken.

“Portside, ahead,” said Duffy, shielding his eyes. “Good Lord… what is she?”

Striding along the bank, precisely keeping pace with the slow-churning boat, was a figure of supernatural symmetry. She moved like a dancer, yet with the hauteur of a queen. Bronze skin gleamed. Her smile, dazzling. Her eyes, fixed on the boat, bore into the deck like searchlights.

Duffy’s feet began to move of their own accord. Beside him, Fitz, had been whining and pacing for some time. Now he sat bolt upright. Then, with eerie calm, lay down as if receiving a silent command.

Duffy was halfway to speech—some invocation of admiration, likely his undoing—when Kamau seized him from behind and clamped a hand over his mouth. With the ease of a rugby man, Kamau hauled him bodily through the galley doors where Lord Thornton was tapping his lip with a pencil, composing what appeared to be a romantic anecdote about his affair with the lovely pastry chef at the Savoy..

“What the devil are you doing, Kamau?”

“Saving your lives,” Kamau replied, breathless. “Trevor next—he’s halfway under already.”

Indeed, Trevor had drifted to the portside rail, watercolour brush dangling from one hand, his gaze vacant with adoration. Kamau leapt back into the corridor, grabbed the young man by the collar, and dragged him inside as if rescuing a fainting debutante.

“She’s working a spell,” Kamau said grimly, drawing the portside curtain. “A proper one. A Bantu Priestess, or worse. Possibly of the M’boko order. Gentlemen—eyes front.”

But too late.

There was a whistle—sharp and unnatural—and then, with the velocity of an Olympian javelin, a spear came hurtling from the jungle.

“DOWN!” cried Kamau.

With a collective yelp, the Chaps hit the floor as the spear buried itself deep in the deck with a resonant THWACK.

By the time they looked up, the enchantress was gone, her form melting into the forest like smoke.

Kamau sprinted upstairs, half-certain he would find the skipper ensnared by the siren’s spell, only to discover Mudge, back turned, pouring Cognac into his mug of coffee.

“Thought you’d gone overboard,” Mudge muttered. “Fancy a dram?”

That evening, Kamau poured stiff whiskeys for the shaken crew while they swapped florid accounts of how each had personally resisted the seduction (none mentioned Kamau’s heroics). Meanwhile, Kamau knelt over the embedded spear. A long the shaft, near the beeswax binding, were carvings—symbols almost like script.

“Duffy,” Kamau called. “You’ve been working through the dialects. What do you make of this?”

Duffy peered, swirling his whiskey and said, “Well, loosely… very loosely… ‘Our Man welcomes you to our village. Bees protect his invitation.’”

Kamau narrowed his eyes. “All that from four symbols?”

“Well,” said Duffy, “a certain interpretive liberty—”

But Kamau had noticed a glint within the beeswax. He carefully peeled it away, revealing a sheet of folded paper. Written on the stationery of the Hotel Stanley in flowing but desperate script:

“Bring more film! Tell Colleen, I regret… nothing.”

The boat chugged on.

Near sunset, Mudge’s voice echoed down the voice pipe—a polished brass relic of nautical engineering, twisted like a horn through the decks:

“This is the Captain speaking. There’s a Banyan tree ahead—magnificent one. Port bow. We’ll tie off and anchor here for the night.”

Kamau turned serious. “Gentlemen, tonight I must insist: stay in your quarters. Lord Thornton?”

Ruffles nodded, unusually grave and added, “We are not equipped to resist their enticements.”

Kamau said, “I’ve spoken to our Mechanic—Moses. He’s indifferent to beauty. That’s not opinion; it’s pathology. He’ll be patrolling on deck with a rifle from our armory.”

That night, in their cabins:

—Trevor read himself into drowsiness with a damp copy of a biography Louis Daguerre: “The Quiet Frenchman.”

—Duffy composed a letter to the British Archaeological Society in Cairo, explaining that, based on his observations of the landscape of the Congo, he’d like to present evidence of a lost civilisation concealed beneath the dense jungle canopy—one that rivalled dynastic Egypt. With adequate funding, he proposed to organise an investigative expedition.

(In retrospect, Duffy’s hypothesis proved oddly prescient. His “observations”—made with no more than a field notebook and a pair of opera glasses—anticipated, by decades, the eventual discovery of pre-colonial urban settlements in the Amazon and Congo basins using LiDAR. Naturally, he considered this validation, though he insisted the technology lacked “the human touch.”)

—Kamau, pacing in pajamas and his threadbare fez, memorised aloud the ingredients of a Chantilly cake recipe with whipped cream topping.

—Lord Thornton snored robustly, his journal tucked into the crook of his elbow like a bulldog pup.

Chapter VI:

From Banyan to Kingdom

Morning arrived soft and golden, with the river steaming gently and birds calling out like half-remembered dreams. The Chaps assembled in high spirits over a breakfast Kamau had dubbed “Continental with colonial inflections.” Lord Thornton declared it “a bit of the all right,” and proposed—over pawpaw and condensed milk—that they make the day’s first order of business the resumption of the Rory Affair.

At precisely 07:20 a.m., Kamau stepped ashore to untie the mooring line from the banyan root, which had served admirably as a natural quay. He was halfway through a sailor’s hitch when his eyes narrowed. There, carved into the smooth belly of the tree’s aerial root, were four familiar symbols—identical to those etched onto the spear that was now mounted, quite dramatically, above the galley mantle.

He stood, called out. “Duffy! Ashore. Now.”

Duffy appeared moments later, boots unlaced and spectacles fogged with breakfast tea. “What is it?”

Kamau pointed. “Same markings.”

“And here,” he added, pulling back a flap of beeswax, lodged in the crook of the root, “a second message.”

It was, once again, folded into a neat triangle of Hotel Stanley stationery, its edges soft with sweat and jungle air. Kamau unfolded it carefully. The writing was familiar: Rory’s fast, impudent script: “Bring a ration of whiskey. Mosquitoes worse than Tanganyika. If you’ve found this message, follow the path from the banyan to My Kingdom.

As Ever, R.”

Below it, in smaller letters, a postscript: “PS: Tell Trevor not to pack the champagne in the camera case again. It makes the negatives taste funny.”

Kamau and Duffy shared a glance. No doubt remained.

“Rory,” said Kamau, “is ahead of us.”

Chapter VII

The Rope and the Ruse

By 08:00 a.m., the expedition had been outfitted.

Lord Thornton insisted on a full load-out, which included:

Mosquito netting (assorted sizes)

Three tripods (one broken at the hinge)

A collapsible canvas table

Four field chairs (one of which Trevor deemed irreparably bourgeois)

A brass-handled megaphone

Seven tins of Queen Mary’s Blend

A parasol for Trevor’s plein air painting sessions

A satchel of monogrammed napkins, slightly yellowed but freshly pressed

Trevor protested none of this. “This is a rescue,” he said, hoisting his Leica. “Not hardship.”

Kamau, on the other hand, was more circumspect. He reviewed the party with the expression of a man watching amateurs prepare a doomed alpine ascent.

“Gentlemen,” he said, tapping the megaphone for emphasis, “the final approach will require discretion. Moses has offered to lead us to the village, but on one condition: we are to be blindfolded.”

A murmur passed down the line.

“A bit much, don’t you think?” Lord Thornton muttered.

“Standard practice for jungle matriarchies,” Kamau replied. “And I’m afraid it’s non-negotiable.”

So it was that, by mid-morning, The Chaps found themselves tethered in single file to a length of thick rope, blindfolds tied with varying degrees of tightness and protestation. Moses took the lead. The porters fell in at the rear, and Kamau stationed himself in the middle to preserve order.

The jungle closed in. The path narrowed. Footing was uneven, and branches slapped at sleeves and shins with unrepentant glee.

“Is this entirely necessary?” Lord Thornton called from somewhere in the middle.

“It is if you value your life,” Kamau answered. “Or your virtue.”

They trudged on, tangled in nettles and complaint.

Then, without warning, the rope went slack.

A cascade of confusion followed. Someone stumbled. Someone swore. The line collapsed like a folding chair.

“Kamau?” Trevor’s voice came from the right.

“Hold position!” Kamau barked. “No peeking, gentlemen! Your lives may depend on it!”

A beat. Then, softly:

“Moses? Moses, where the devil are you, man?”

There was no answer. Only the steady, shrill trill of cicadas and the broad, oily rustle of palm fronds in the heat.

Then a musical voice. Female. Close. Enticing.

A shuffle of feet on the path. A crate hitting the ground. Laughter.

A man’s voice, speaking M’boko. Then another.

Lord Thornton: “Bloody hell, she’s seducing the porters!”

Quiet fell, save the insect orchestra.

Kamau muttered, “Stay calm, boys—er, Bwana—let’s keep our heads.”

Trevor, dryly: “Splendid advice.”

Kamau untied his blindfold and draped it over his head like a mourning veil. He turned with care, groping his way along the rope.

“Excuse me... oh, terribly sorry... is that you, Duffy?”

He passed each man, shuffling backward through the disorder. At the end of the line, Kamau tripped over two abandoned crates.

He crouched.

“Make that two porters seduced.”

Duffy, from somewhere behind a thorn bush: “My God, they must be all around us.”

Kamau stood slowly. “Correct assumption. Blindfolds on, gentlemen. I’m retaking the lead. We’re returning to the Congo and our home—the Roi d’Élégante.”

Grumbles rose from the undergrowth. But the rope tugged forward, and one by one, the men rose and resumed the line, their dignity unspooling like so much mosquito netting.

At a bend in the path, Kamau called out: “Halt. Eyes forward. You may remove your blindfolds.”

They did. A pause. Sunlight broke through the canopy like a reprieve.

Lord Thornton cleared his throat. “This is a shameful episode for all of us. I propose we make a pact—another gentlemen’s agreement. If we manage to find our way back to civilization, we never speak of this again.”

Trevor: “Where the hell’s Moses?”

Duffy: “Gentlemen... we’ve obviously been betrayed.”

Lord Thornton, eyes widening: “My God. The boat! Fall in behind me. Double-time pace. We must get back to the boat.”

They broke into a haphazard jog, crashing through foliage, tripping over vines, wheezing and cursing and praying.

When they reached the great banyan tree where the Roi d’Élégante had been moored, they found only the hush of water, the echo of insects, and a long stretch of empty riverbank.

The boat was gone.

Chapter VIII:

Lost Along the River’s Edge

They stood in silence at the edge of the water, eyes sweeping the river like mourners scanning the pews for the dearly departed. The Roi d’Élégante had vanished.

“It’s inconceivable,” Lord Thornton whispered. “Boats don’t simply... vanish.”

“Tell that to the Mary Celeste,” Trevor muttered.

Duffy said nothing. He had crouched beside a mangled bit of rope, as if it might speak to him.

Kamau straightened, hands on hips. “We camp here tonight. No use marching blind into dusk. We’ll track along the river tomorrow.”

And so, they made camp under the great banyan tree. A sorry little bivouac, composed largely of failed intentions. The mosquito netting had been left behind. The megaphone was dented. Of the Queen Mary’s Blend, only one tin remained—and it had been punctured.

Bats emerged at twilight—great flapping silhouettes that darted above the firelight. Trevor, who had taken to lying flat on his back, muttered, “I’m being strafed.”

Lord Thornton was attempting to heat water in the lid of a field kettle. “It’s an intolerable racket. Those damned cicadas sound like buzz saws.”

“Could be worse,” Duffy offered. “We could be back in Brussels.”

Kamau had gone quiet, sitting cross-legged beside the fire, eyes reflecting flame and thought. “The boat was taken deliberately. No signs of struggle. No wreckage.”

Trevor rolled over. “By whom?”

Kamau shrugged. “Priestesses.”

Lord Thornton scoffed. “You mean to tell me that an order of jungle debutantes has outmaneuvered a crew of two and a steamer full of provisions?”

“Not debutantes,” Kamau said. “Commandos.”

Silence. The fire popped.

Duffy opened the punctured tin and tried to coax leaves into a tepid infusion. “One assumes they’ve taken Rory as well.”

“If they have,” said Kamau, “he’s either their king—or their captive.”

The next morning, they set off at first light, hugging the riverbank, hoping for tracks, for smoke, for something that looked like hope. The jungle was thick with green hostility. Their boots sank into soft earth. Trevor carried a chair leg as a walking stick. Lord Thornton, silent for the first time in recorded history, muttered only to himself.

By late afternoon, the river widened into a still, glassy expanse. Kamau raised his hand.

“Hold position. Do you see what I see?”

There, rounding a bend in the river, cloaked in mist and impossible grace, came the Roi d’Élégante.

She was gliding upriver like a returning queen.

At the helm—Rory.

On deck—eight priestesses. Each stunning. Each poised. Each manning a post with casual authority.

The Chaps froze. One or two ducked into the foliage.

“Is it... is it safe?” Trevor whispered.

Kamau nodded slowly. “For now. They’re under orders.”

“From whom?”

“Him.”

They emerged like chastened schoolboys.

The gangway was lowered with deliberate grace.

At its head stood a priestess in her traditional regalia—golden gauntlets coiled up her forearms like serpents in mid-embrace, layers of necklaces veiling her bare breasts, and rows of shimmering glass beads cascading from her collarbones. Her gold leggings gleamed up to the knee, catching the light like beaten shields, while her thick, obsidian hair was laced with feathers, charms, and talismans that whispered when she moved. She did not merely belong to the wilderness—she was the wilderness, distilled and adorned.

She smiled down at me with a poise that unstrung the bones from my knees, and extended a hand—half invitation, half incantation—welcoming me aboard. I gathered what remained of my composure and accepted her hand, trying not to look as if I’d just been hexed by a particularly glamorous tree spirit.

Back on board, the air smelled of lemongrass and order. The brass had been polished. The parasol replaced. Fitz had been bathed and wore a ribbon.

Rory, crisp in a linen shirt and barefoot at the wheel, grinned like a man who had not only been rescued, but redeemed.

“You boys look dreadful.”

Lord Thornton blinked. “You’re… in charge?”

Rory laughed. “They needed a skipper. I passed the audition.”

Kamau folded his arms. “And Moses? Mudge?”

Rory hesitated. “They were… relieved of duty. Nothing violent. Just… spirited away. I’m told they’ll re-emerge, slightly confused and fond of poetry.”

The Roi d’Élégante steamed on.

And not a word, not a single word, was said of the rope.

Chapter IX

The Ivory Lounge

Matadi, a week later.

The Stanley Hotel was the kind of place where the ceiling fans never worked, but the piano did. The wallpaper curled at the corners like old postage stamps, and the gin tasted faintly of mango soap. None of it mattered.

The Chaps were alive.

They occupied a low velvet banquette in the hotel’s Ivory Lounge, a room perfumed by age and something not unlike mothballs. The ceiling dripped with chandeliers of questionable wiring. An out-of-tune jazz trio played in the corner with great sincerity and no rhythm.

Lord Thornton sipped his drink and sighed. “Say what you will, but there’s something to be said for a weak gin and a strong ceiling.”

Trevor, now bathed, shaven, and re-collared, leaned back against the wall. “I feel I’ve shed not just mud, but a layer of Victorian guilt. I may never paint in England again.”

Kamau was engaged in picking the seeds from a segment of mango with surgical precision. Duffy was sketching on a cocktail napkin, capturing the lean curve of a bamboo fan.

There was a murmur at the door.

Rory entered.

He wore a tan linen suit and the relaxed expression of a man who’d found whatever it was he hadn’t been looking for. On his arm was one of the priestesses, discreetly dressed for hotel protocol, but somehow even more luminous in restraint.

Conversation halted.

Every head turned.

The pianist dropped a chord. The ceiling fan started, groaned, and gave up.

Lord Thornton stood. “Good lord. She’s breathtaking. And she’s his girlfriend.”

Rory gave a modest bow.

“We thought you’d gone native,” Trevor said, standing to shake his hand.

“Worse,” Rory replied. “I’ve gone monogamous.”

Laughter erupted. Drinks were poured.

Lord Thornton raised his glass, his voice rich with ceremony and gin:

“To our rescuer—and dare I say, the Tamer of Bantu Priestesses. May his compass always point toward danger, and his steamer never run aground.”

Glasses clinked.

The jazz trio launched into something vaguely recognisable. The ceiling fan wheezed to life.

And Duffy, always scribbling, noted quietly in the margin of his napkin:

Nothing civilised, nor savage, ever truly ends. It merely changes costume and takes the next boat downriver.

Fin