The Horn of Africa in E-Flat

Being an Account of Certain Curious Events Following a Railway Complication, with Particular Reference to Lions, Ladies, and Luncheon in the Bush...

“Adventure is simply inconvenience rightly considered.” —G.K. Chesterton

Dramatis Personae

* Duffy Whitmore – Our narrator; English, observant, slightly faded around the edges, but in a flattering way.

* Trevor Finch-Bligh – Of ancient stock and uncertain usefulness. Knows a great deal about port and very little about anything else. Unfortunately Trevor couldn’t join us on this outing. He’s got a room in Wetzlar, Germany, across the street from Leica’s headquarters, to be close to his rangefinder while it’s undergoing repairs.

* Lord Thornton (“Ruffles”) – A peer of the realm and of the lounge car; good with languages, unbothered, unfussed, occasionally moustached.

* Rory Maher – From Dublin. Maher is pronounced Mar. Cool-headed, quick-witted, occasionally mistaken for someone who knows what he’s doing.

* Daphne, Rosalind & Marigold – English Roses in the wild; practical, unflappable, and, when necessary, armed.

* Kamau – Ruffles’ man in Nairobi. Possesses preternatural calm, logistical genius, and a fine hand with tartlets.

And so it begins…

The train shuddered to a halt somewhere between Eliphazi Junction and what the timetable optimistically called King Solomon’s Siding. Outside, the veld was a bleached, brittle expanse—a mixture of acacia, anthills, and infinite disinterest. We were told the engine had suffered “a complication of parts,” which we understood to mean something had exploded.

The lounge car, our sanctuary from the dry heat and the smell of boiled goat wafting from the dining carriage, was mercifully underpopulated. Ruffles had commandeered the banquette under the electric fan and was making a spirited attempt to cool his wrists with the condensation from his gin. Rory was engaged in a battle of wills with a wasp and losing. I was leafing through a railway magazine full of stories about tunnels, which seemed grotesquely optimistic under the circumstances.

“I say,” Ruffles began, tapping the heel of his boot against the ice bucket. “If this train is going nowhere—and all evidence suggests that it is—we might consider a small diversion.”

Rory looked up, his tie slightly askew. “You mean alight? Now?”

“No, no, don’t be literal, Mr Maher. I propose we go on safari. There’s no use in sitting here brooding. I’ve sent a message to Kamau to fetch the Rolls and requested he stay on to assist us in the bush—you know, changing tyres, serving tea, drinks after five. Iced gin. Hors d’oeuvres. That sort of thing.”

There was a silence, broken only by the fan’s wheeze.

“Kamau is in Nairobi,” I reminded him gently.

“Yes, but he has the keys to my Rolls. And, more importantly, a sense of duty. The message is on its way now with one of the dining porters. Promised him half a tin of pipe tobacco. Worked like a charm.”

Rory blinked. “And we’re just… going?”

“Well, we’ve packed nothing,” I said, “but then again, neither did the Imperial Yeomanry. And look how well that turned out.”

Kamau arrived at dawn the following day, as if summoned not by message but by meteorological inevitability. The train had not moved an inch, but a dust plume on the horizon announced his approach long before the silver of the Rolls-Royce came into view.

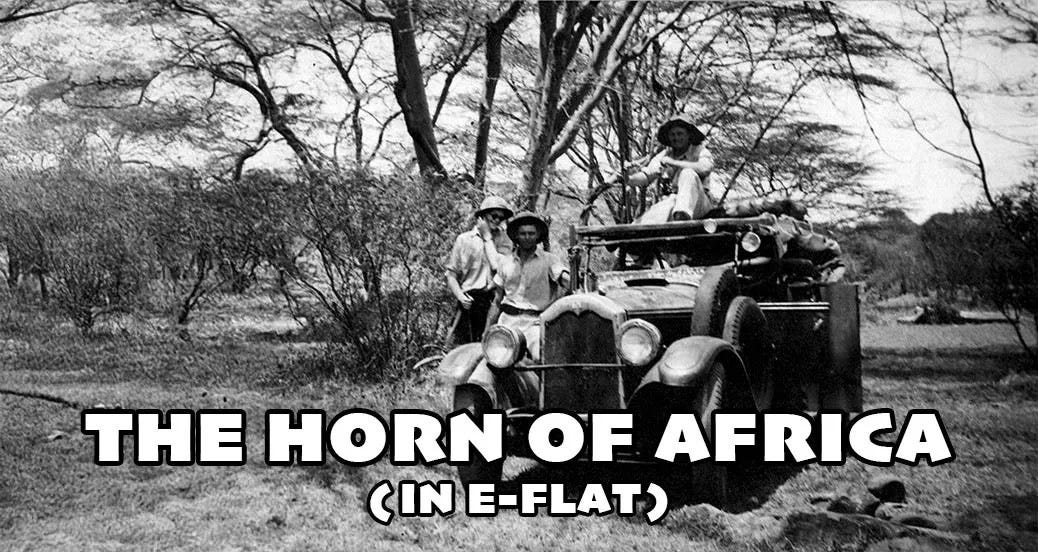

It was Ruffles’ safari Rolls—custom-bodied, of course—with elephant-hide upholstery and a rack of long rifles that had never been fired but looked awfully authoritative in silhouette. Kamau wore his usual expression of diplomatic amusement, and behind his sunglasses one imagined the slow blink of a man resigned to aristocratic absurdity.

We emerged from the lounge car in various stages of readiness. Rory had his monocle tucked into his shirt pocket (he said it was for navigating by sun angle), and Ruffles was in what he called his “light tropics kit”—immaculate whites and a cork helmet that had never seen a battle beyond the glare of hotel verandahs. I had a battered notebook and a fresh cravat.

Kamau stood beside the open boot of the Rolls, revealing a safari kit of comical perfection: canvas tents, mosquito netting, wicker lunch hampers, collapsible cocktail tables, a twin-burner stove, gramophone, cargo shorts folded just so, and a case marked “Gin: Urgent.”

“How does he manage it?” Rory whispered, as Kamau secured a lemon crate with a loop of sisal and nodded for us to climb in.

“We’re in his world now,” said Ruffles, sinking into the leather seat with a contented sigh. “Best to let him drive.”

Near dusk on the first day, with the bush turned gold and all sensible creatures retreating into thorny anonymity, we came upon an encampment nestled beside a dry riverbed. It was neat. Too neat. The guy ropes were taut, the canvas immaculate, the fire pit ringed with polished stones. And emerging from the largest tent, in pressed khaki and sun-faded safari hats, came three figures—each one an English Rose in full bloom, their cheeks sun-kissed and their manner unflustered, even at the sight of three unshaven men and a gleaming Rolls parked like a visiting diplomat.

There was something instantly formidable about them—not in a harsh way, but in that terrifyingly competent fashion unique to certain women who grew up with governesses, field hockey, and one rifle per child.

We introduced ourselves with the bashful theatricality of schoolboys at a village fête. Their names were Rosalind (tall, quiet, with eyes like conspiracy), Daphne (shorter, sharper, very possibly in command), and Marigold (a vision of effortless grace with a habit of refilling one’s glass before one noticed it empty).

“We weren’t expecting visitors,” said Daphne, raising an eyebrow.

“Neither were we,” said Rory, dusting his lapels. “We were expecting a train.”

Dinner was taken beneath a sky so clear it might have been laundered. Kamau, having unearthed a folding dining table from the rear of the Rolls, produced a meal so sophisticated it might have been served in the Palm Court of the Savoy—had the Savoy allowed wildebeest in the vicinity. Chilled avocado with lime, cold roast beef, something involving anchovies and artichokes, and a lemon tart so airy it might have been flown in from France.

“I say,” whispered Rory, as Kamau shaved ribbons of ice from a block wrapped in flannel. “How does he manage it?”

“I suspect magic,” I said, reaching for the Worcestershire.

Conversation flowed in elliptical orbits, brushed by laughter and smoke. Marigold had once studied botanical illustration in Florence. Rosalind claimed to have driven a mail truck in Tanganyika. Daphne, rather chillingly, referred to “a misadventure in Abyssinia” and then refused to elaborate. The gin sparkled, the moths fluttered, and the air grew soft with promise.

By ten o’clock, the table had been cleared, the fire stoked to a polite blaze, and Kamau had withdrawn to his corner to perform the gentle alchemy of camp washing-up—his silhouette haloed in embers and dignity.

That’s when the growl came.

It was not the polite complaint of a discontented jackal, nor the muttering of distant hyena politics. It was deep and dreadful, the kind of sound that reorders one’s relationship to nature and trousers simultaneously. It came again—closer this time—and was followed by the unmistakable rustle of heavy bodies in the undergrowth. The firelight flickered. The gin turned to water in our glasses.

Rory stood up and sat down again without instruction. Ruffles gripped the armrests of his chair with the pale-knuckled resolve of a man awaiting dental work. I was frozen somewhere between flight and narrative detachment.

The ladies, by contrast, did not move. They merely exchanged a look. Rosalind nodded. Marigold rose and moved calmly toward their customised Buick—an angular, sand-coloured thing that looked like it had opinions on fencing and jazz. From its front seat, she retrieved a device that looked like the love child of a bugle and a tuba, lacquered in pink and stamped with something in brass.

“What in God’s name is that?” I whispered.

“Our horn,” said Daphne, standing now.

She gave a low whistle. Marigold nodded once, and then—with all the poise of a duchess christening a destroyer—pressed the horn.

The sound it emitted was indescribable. Not a honk, not a blare, but something baroque and obscene—like a mating call between a ferry and a dying moose. It rolled out into the night like a tsunami of poor taste and instinctive terror.

The lions scattered. One could hear the confusion in the brush. The growling ceased.

“Learned that one in Tsavo,” said Rosalind, dusting her hands. “Lions can’t stand a mechanical E-flat.”

The next morning over strong coffee and something Kamau called Mandazi but Better, the ladies explained their invention. During a prior safari, they’d found themselves under threat from a similar pride. Lacking reinforcements and with only a dismal .303 between them, they’d resorted to the horn of their vehicle. The reaction was immediate: lions fled, guides fainted, and a rather good recipe for banana bread was lost in the shuffle.

After returning to Nairobi, they partnered with a Scottish engineer named MacDougal (retired from Klaxon), and the Horn of Africa was born: a handheld brass instrument, absurdly loud, tunable to dissonant registers, and available in six designer colours. Proceeds went to elephant conservation and the Anglican Mission School for Practical Girls.

“We’ve had marvellous success,” said Daphne, examining her nails. “Harrods stocked them for a time, but there were complaints from Knightsbridge.”

The train, miraculously repaired by someone who’d clearly studied with Saint Jude, collected us three days later. We reboarded with the weary dignity of veterans returning from a war in which we’d barely served.

That evening, as the train rolled past baobabs and the last pink light dissolved into the dust, we took our usual places in the lounge car. Ruffles ordered something restorative involving Dubonnet and a twist.

“Obviously,” he began, twisting the end of his moustache with solemn grace, “our behaviour was disgraceful and we shan’t mention it again. Agreed?”

“Agreed,” said Rory, who had joined us halfway through and still smelled faintly of lemon oil and gun polish.

“Of course,” I said. “It’s already forgotten.”

Ruffles went on. “Now, as to the other matter. We must assume the ladies will giggle and gossip about this episode, and that our names will be attached to it, possibly in print. The best strategy is to admit we were there, but tell a slightly different story.”

Rory stirred. “What version?”

“We all panicked, including our hosts, which of course is a lie, but only a tiny one. We say it was Kamau who had the presence of mind to honk that blasted horn.”

“Did he?” asked Rory. “I was staring at the blackness beyond the fire.”

“No,” I said. “He was washing up.”

“That’s true, Duffy, he was washing up,” said Ruffles, sipping. “But I have new information. Not an hour ago, when Kamau was about to depart for the journey back to Nairobi, he walked me back to the Rolls’ boot and flipped back a corner of the canvas cover to reveal, securely nestled in its place, a Horn of Africa.”

“Good heavens,” I said.

“It was enamelled in semigloss crimson, the colour of dried blood on a Kenyan dirt road—his favourite colour,” Ruffles continued. “Unbeknownst to me, Kamau had purchased the horn a year ago with petty cash from the kitchen jar and it has been aboard the Rolls all that time.”

“Bless him,” Rory said.

“While washing up he was waiting for us to take charge of the situation, which, of course, we didn’t, and just as he was about to get his horn from the boot and give it a good blast, Marigold marched over to their Buick and retrieved their horn, which, as it turns out, Kamau knew all about—he spotted it on the seat of the Buick, as he was going to and fro setting the table for dinner.”

“He was actually waiting for the ladies to use their horn first,” Rory exclaimed.

“Correct,” said Ruffles. “So, although it’s a fib, I propose we give Kamau the story. After all, he was prepared to blast the wilderness with E-flat, in the event everyone else failed in their duty—and he’s the only one of us who behaved like a man.”

–– Duffy Whitmore