The Luncheon at Roquetaillade

• A Duffy Whitmore Adventure •

Epigraph

“The traveller’s virtue is exactness; the pilgrim’s, persistence. One must choose daily which to be.” — T. E. Lawrence, field notebook, 1908

Editor’s Note by Duffy Whitmore

In the summer of 1908, a nineteen-year-old Oxford undergraduate named T. E. Lawrence set out alone upon a second-hand bicycle and pedalled two thousand miles across France. His purpose was archaeological rather than athletic: to examine and sketch medieval castles for his thesis on Crusader influence in European fortifications. He began at Tours, drifted south through the Dordogne and Gascony, sketched Carcassonne in a state of rapture, and followed the Rhône northward again toward Avignon and the Loire. He travelled cheaply, slept seldom, and wrote home constantly—letters that read like blueprints for his later legend.

It was this enterprise—half scholarship, half pilgrimage—that Trevor Finch-Bligh and I elected to emulate some twenty years later, reasoning that, if Lawrence had found revelation on two wheels, we might at least find luncheon. What follows is an account of that modest retracing: two Englishmen, a Leica, and an excess of faith in the reliability of French tyres.

Chapter I — Bordeaux, Maps, and Self-Deception

(1928 — or thereabouts)

“I travel very slowly, for the country is too good to pass in haste, and every castle demands the courtesy of a sketch.” — T. E. Lawrence, letter to his mother, 1908

I have always maintained that a gentleman should arrive in a city by water if at all possible; it softens the aspect and obliges the skyline to put its best chimneys forward. Bordeaux, obliging as ever, received us with a glazed wink off the Garonne and a smell of wine barrels so frank that Trevor Finch-Bligh declared himself “virtually intoxicated by terroir” before luncheon.

We had come to cycle — which is to say, to move about slowly in the manner of serious men — with the stated purpose of retracing T. E. Lawrence’s youthful reconnaissance of medieval castles. Trevor, who takes the long view when the long view is romantic, called it “a knight-errant’s pilgrimage upon pneumatic tyres.” I, who take the long view when it has shade, settled for “a pleasant tour with occasional masonry.”

Our machines, purchased that morning from a shop whose proprietor addressed them as if they were horses, were equipped with bell, lamp, and a species of luggage contraption that made each bicycle resemble a particularly earnest beetle. A Leica hung from my shoulder in the manner of a moral obligation. Trevor strapped his sketchbook to his handlebars so that everyone might know there was genius about.

We established headquarters at a riverside inn with white cloths and a wine list that behaved like a staircase. The innkeeper produced maps with the entreating air of a conjurer who fears his rabbits have been oversubscribed. Trevor instantly spread them like battle plans and began tracing an elegant serpentine from Bordeaux to the hill-towns of Gascony, thence towards Carcassonne, thence to the high forts where, according to him, “the Middle Ages still keep a pied-à-terre.”

“You observe,” he said, tapping a bastion with the stem of his pipe, “that Lawrence passed within a mile of Roquetaillade on the third day. One imagines him pausing, gaze lifted, the whole chivalric enterprise crystallising in a single, sun-struck instant.”

“Mm,” I said, examining the dessert menu. “And one imagines him sleeping heartily thereafter.”

Trevor does not dislike my empiricism; he simply ignores it as one might ignore a polite waiter. He continued: “We shall carry only what is essential — a spare tube, a map, a shirt for civility, and the spirit of inquiry.”

“Add socks,” I said. “The spirit of inquiry notoriously blisters.”

We undertook a trial lap along the quay to discover whether our equipment intended to collaborate. Trevor’s bell rang with a tone of moral uplift; mine produced the discouraged clink of a curate’s teacup. Children cheered. An elderly gentleman, seeing our plus-fours, removed his hat, either in respect for tradition or in astonishment at its survival.

The air was that agreeable April compromise which suggests exercise without requiring it. Trevor pedalled with the uplifted chin favoured by equestrian statues. I kept a log of observable phenomena: (1) cobbles resist optimism; (2) the Garonne flows to sea; (3) wine-merchants at eleven in the morning look as if they have always just completed something significant.

Back at the inn, we took inventory. Trevor’s pack contained: a collapsible drafting ruler, a guide to Romanesque sculpture, three pencils aligned with military precision, and a tin of biscuits labelled Army Issue — Do Not Complain. Mine contained: socks, a small bottle of iodine, a notebook, and a phrase in French calculated to obtain breakfast in circumstances bordering on siege.

“To Lawrence,” Trevor said, raising a glass.

“To level gradients,” I replied, and we drank to both.

After luncheon Trevor insisted upon a ceremonial reading from his pocket Lawrence — the early letters in which the young scholar describes cycling towards castles as if toward a moral appointment. The passage did its work: even the cutlery felt suddenly medieval. We sat in the window, watching the river go past as though it were time itself and we had booked seats.

A boy arrived with a parcel tied in string — our last-minute acquisition from the bookseller: a hand-measured copy of an 1890s touring map annotated, the seller claimed, by a local antiquary who had once guided a certain English undergraduate of promise. Trevor stroked the margin as if it might purr. I peered at the handwriting and concluded that the antiquary had been either left-handed or chased.

We fixed our departure for the morning. Trevor proposed reveille at six; I counter-proposed seven with coffee, which he accepted on the grounds that a knight may break his fast without loss of face. The bicycles were stabled in the hall, where they leant against the umbrella stand like conspirators pretending innocence.

Evening brought that particular Bordeaux light which arranges itself upon façades as though attending a lecture. Trevor discoursed on machicolations and arrow slits; I photographed the wine glasses, which were perfectly designed for the retention of history. We consulted the weather, found it promising, and the bill, found it historical.

“I confess,” Trevor said at last, staring into the river, “that one feels a summons.”

“From Lawrence?”

“From architecture. He merely translates.”

“Then we shall translate also,” I said, “with frequent notes.”

He smiled in a way that accepted my heresy as useful ballast, and we parted for our rooms — he to dream of keeps and banners, I to lay out socks with the gravity such things deserve.

Thus armed — with scholarship in Trevor’s case and luggage in mine — we prepared to make the acquaintance of France at the exact speed at which she could forgive us.

Chapter II — The Historian of Bazas

“One learns more of fortresses by climbing their ditches on a bicycle than by reading of them in libraries.” — T. E. Lawrence, letter to his father, 1908

We left Bordeaux the next morning at the hour favoured by milkmen and moralists. The city still yawned itself awake as we rattled across the bridge, our tyres emitting a faint hymn of purpose. Trevor led with the confidence of a general whose map is upside down; I followed at a journalist’s pace, which is to say, far enough behind to preserve objectivity.

The road south unfurled with the self-satisfaction of a cat in the sun — vineyards, poplars, and the smell of yesterday’s bread. We stopped at intervals to admire the horizon and to give Trevor opportunities to declare it “Lawrencian.” My own interest lay chiefly in the discovery that every French café, however small, has a patron who appears to have been waiting there since the Restoration.

By noon we entered Bazas, a medieval town so picturesque that it had begun to suspect itself of forgery. Its cathedral dominated the square like a well-fed conscience. We tethered our bicycles to a cannon of the 1870 variety and took refuge in a café whose proprietor was engaged in an unequal struggle with a gramophone.

Trevor unfolded the map upon the table. “Here,” he said, “Lawrence paused to sketch the south portal — a masterpiece of Flamboyant Gothic. One can feel his excitement in the stone.”

“Possibly,” I said, “but I suspect he felt his excitement mostly in the saddle.”

While we debated the theological implications of chain lubrication, a man at the next table — portly, tweed waistcoat, spectacles tethered like livestock — leaned over.

“You are English gentlemen?” he asked in that tone the French reserve for the clinically eccentric.

Trevor beamed. “Travellers,” he said. “We follow the route of T. E. Lawrence. The castles of the south.”

The man introduced himself as Monsieur Arnaud, a local historian “of limited fame but unlimited accuracy.” He claimed to have corresponded with “a certain Oxford youth” who had indeed visited Bazas before the Great War, “to make drawings of the portal, very precise, very strange.”

“He spoke little,” Arnaud said, “but he asked many questions about the tower at Roquetaillade — whether there were writings upon the stones, symbols, marks of a secret brotherhood. I told him no, but he smiled as if the answer were yes.”

Trevor leaned forward, eyes alight. “Did he return? Did he write to you?”

Arnaud shrugged. “He sent one postcard. It said only, ‘One page missing.’ I thought perhaps he had torn a leaf from his notebook.”

Trevor and I exchanged the look of men who have just heard destiny mispronounced.

“One page missing,” Trevor repeated, as if testing a relic for authenticity. “Duffy, don’t you see? The unpublished fragment — a castle he found but never named!”

I did not see, but it seemed unkind to say so in front of the witness. Arnaud, encouraged, leaned closer.

“They say he saw something at Roquetaillade that changed his mind about fortresses. He stopped writing of walls and began writing of winds.” He tapped his temple. “Mystical, perhaps.”

Trevor was radiant. “Mystical and architectural — the only acceptable combination.”

I ordered another coffee to steady the empirical world.

When we left the café, Trevor was already marking a new line upon the map, a detour eastward into Gascony. “Roquetaillade,” he said, “the missing page. We must see it.”

“Must we?” I asked.

“Lawrence did not turn back, Duffy. Nor shall we.”

I reflected that Lawrence had also learned Arabic and joined a war, which suggested a certain bias toward inconvenience. But Trevor had that glint which renders argument merely decorative. He adjusted his goggles, looking absurdly gallant, and pedalled off toward the horizon.

I sighed, mounted my bicycle, and followed, the map flapping behind me like a surrender flag.

Chapter III — Roads, Revelations, and Reparations

“The Château Gaillard was so magnificent, and the post cards so abominable, that I stopped there an extra day and did nothing but photograph from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m.… I will certainly have to start a book.” — T. E. Lawrence, August 1907

By the second day of our detour, Gascony revealed herself as a land of undulations — each hill a polite but firm suggestion that the next would be worse. Trevor rode ahead, the wind tugging at his sketchbook like divine dictation, while I observed from a safe distance that every medieval castle had been designed by sadists who disapproved of gradients.

Our map, annotated by Monsieur Arnaud with what he called “minor inaccuracies,” was in fact a work of pure imagination. Half the roads existed only in the optimism of cartography; the rest led to farms guarded by dogs of such moral seriousness that we adopted circuitous routes out of respect for agriculture.

At Casteljaloux, a blacksmith repaired my rear tyre with the serenity of a priest hearing confession. “Too thin,” he said, slapping the tube. “Made for English weather.” He then produced a piece of rubber that looked like it had once served on an airship. It held admirably, though my bicycle acquired a slight bias to the left, which I chose to interpret politically.

Trevor, meanwhile, recorded each village in his notebook with an ecstasy bordering on the ecclesiastical. “Observe the window tracery!” he would cry, dismounting mid-traffic. “That cusp! That ogive!” The villagers, untroubled by the finer points of Gothic, regarded him as an ambulatory sermon. Children followed at a distance, convinced we were part of a travelling zoo.

One afternoon we took shelter from a shower in a wayside chapel dedicated to St. Gilles, patron of pilgrims, cyclists, and — if not yet, then soon — fools. The interior smelled of rain and candle grease. Trevor, studying a fragment of mural, announced that Lawrence had “stood here, contemplating the mystery of endurance.”

I contemplated the mystery of damp wool. “You think he left the missing page here?”

Trevor smiled, water dripping from his nose. “No, but he would have understood this weather as penance.”

We pressed on through drizzle into Agen, where the bridge over the Garonne shone like a length of pewter. A café offered shelter and omelettes of heroic girth. The proprietress, a woman of indeterminate age but formidable shoulders, eyed our mud-streaked attire with professional pity.

“You seek the château?” she asked. Trevor nodded. “Then you follow the wrong river. Roquetaillade lies east, beyond the vineyards of Sauternes. But beware the old road through Bernos — it climbs like a sermon and descends like a sin.”

She served us wine the colour of late repentance. Trevor, glowing from within, declared that Lawrence himself must have heard those very words, that we were “breathing the same cautions, riding the same risks.” I allowed that we were at least sharing the same wine.

That night we slept at an inn whose walls were decorated with photographs of oxen and local champions of pétanque. Trevor retired early to chart our new course. I lingered with the innkeeper, who explained in confidence that Roquetaillade was haunted — by what, he could not say, though he suspected taxation.

At dawn, the air smelled of wet stone and ambition. Trevor was already astride his bicycle, reading aloud from Seven Pillars about “the clean, holy hardness of physical labour.” I suggested he apply it to the act of pedalling. We set off toward Sauternes, the road rising in long, pious folds through vineyards glistening with dew.

Halfway up a particularly moral incline, Trevor halted, transfixed by the sight of a ruined watchtower on the ridge. “He saw this!” he cried. “Lawrence! The very contour of revelation!”

I was seeing revelation mainly in the form of breakfast. But I humoured him, and we climbed to the ruin, where Trevor discovered, scratched into the lintel, a faint “T”—or possibly a farmer’s attempt at “F.” He took a photograph for posterity and declared it “the first letter of truth.” I took a photograph of Trevor taking the photograph.

By evening we rolled into Langon, our legs mutinous, our spirits undiminished. Trevor spoke of Roquetaillade as if it were Avalon; I spoke of dinner as if it were hope. We found both waiting — the latter on a checkered tablecloth, the former glimmering faintly in the distance like a promise kept to a better generation.

Trevor leaned back, exhausted but radiant. “We’re on the threshold, Duffy.”

“Excellent,” I said. “Let’s knock politely, in case the threshold bites.”

He laughed, and for a moment the rivalry between dream and digestion dissolved. Outside, the bells of Langon tolled vespers, and I wondered whether Lawrence had ever heard them, or merely imagined that he had — a small but crucial distinction which, in our case, made all the difference between scholarship and adventure.

Chapter IV — The Missing Page

“I begin to understand how stone and wind conspire to teach endurance: the towers stand not proudly, but obstinately.” — T. E. Lawrence, letter to Vyvyan Richards, 1908

Morning broke with the clarity of a well-polished mirror and the menace of what it reflected. Trevor was already in his plus-fours, consulting the map as if preparing for a campaign; I was discovering that French coffee, taken at speed, functions equally as inspiration and punishment.

Roquetaillade lay eight miles east — a manageable stretch by bicycle, or a pilgrimage on foot should the bicycles continue their policy of indifference. The road climbed steadily through the vineyards, each bend offering a postcard of the last one. Trevor rode ahead in a posture of revelation, the wind making an icon of his hair.

At the crest of the final hill we saw it: the Château de Roquetaillade, rising out of the mist like an engraving of a dream someone had misfiled. Six towers, grey as thought, and a central keep so symmetrical it appeared to have been designed by geometry itself. Even I felt a certain admiration, though I disguised it as scepticism for Trevor’s sake.

“There it is,” he whispered, stopping his bicycle as one might stop at a shrine. Lawrence’s vision of endurance.”

“Indeed,” I said, “and endurance is the word.”

A gatehouse guard, unimpressed by pilgrims, informed us that the château was closed until two o’clock. Trevor produced a smile that has opened many doors but none that were locked. “We have come in the spirit of scholarship,” he explained.

The man shrugged. “Scholars wait like everyone else.”

We retired to a neighbouring field where the château’s towers loomed above us, apparently studying us for a change. Trevor unfolded his sketchbook; I unfolded a sandwich of uncertain lineage. By the time the gate reopened, both of us were fortified.

Inside, Roquetaillade smelled of age and benevolent neglect. The custodian, a woman of monastic calm, led us through chambers where bats hung like punctuation. Trevor walked with the reverence of a pilgrim entering footnotes.

“Do you see, Duffy? Lawrence must have been struck dumb here — the geometry, the light—”

“Possibly the bats,” I said.

We reached the spiral stair of the tower. Trevor asked if we might ascend; the custodian demurred, saying the upper rooms were unsafe. Trevor, whose sense of destiny outweighs his respect for signage, waited until her back was turned, then whispered, “Just a look. For Lawrence.”

Against my better nature and lower instincts, I followed. The stairs narrowed, corkscrewing toward a slit of light. Halfway up, the air thickened with dust and heroism. At the top, a single chamber — roof partly collapsed, walls scrawled with the efforts of centuries. Trevor advanced to the far wall, brushing away cobwebs like veils.

“There!” he cried, pointing to a faint inscription: three letters, shallowly carved:

T E L

It might have been Lawrence; it might have been local initials; it might, for all we knew, have stood for Très Évident Larceny. But Trevor was transported.

“He was here!” he breathed. “He left his mark — the missing page!”

Before I could dampen the mood with reason, thunder announced itself over the vineyards. A storm rolled in with the efficiency of divine punctuation. Wind pressed through the narrow slit; a loose shutter clattered like applause.

“We should descend,” I said. “History is crumbling in real time.”

But Trevor, determined to photograph the inscription, stepped onto a patch of flooring that had long since declared independence from architecture. There was a creak, a gasp, and a sudden, very medieval noise of splintering. Trevor vanished through a hole, leaving behind his camera and an echo of surprise.

I looked down: he had landed mercifully in a drift of hay or perhaps history. “All well?” I called.

“Entirely!” came the answer, muffled. “I have discovered a substructure!”

“You’ve discovered the ground floor,” I said, descending with as much dignity as a rescuer can muster in a thunderstorm.

By the time we emerged, rain was marching across the vineyards in serried ranks. The custodian stood under the gate arch, arms folded, looking precisely like authority personified. Trevor, dripping and euphoric, tried to explain that scholarship sometimes required unsanctioned enthusiasm.

She handed him his sodden notebook. “In France,” she said, “scholars also use doors.”

We rode back to Langon in silence, the road now a river and each pedal stroke a penance. Behind us, lightning framed Roquetaillade in brief, photographic flashes — our private apocalypse recorded in monochrome.

Trevor finally spoke: “Duffy, I think the initials were real.”

“I think the hole was,” I said.

He smiled, rain streaming off his nose. “It was worth it.”

“Every contusion,” I agreed.

Interlude — The Lady of the Canyon

“With reference to touring in France. There is no doubt that people would cheat you if possible. When we did not get an accurate statement of accounts we got huge bills (this only happened twice).” — T. E. Lawrence, letter to his mother, 1906

The road uncoiled downhill in a shimmer of heat. The storm had rinsed the sky to glass, and the limestone walls on either side of the gorge glowed like bleached parchment. Trevor rode ahead, humming a hymn that may have been Gregorian or merely hopeful. I followed, admiring the geometry of switchbacks and congratulating myself on our progress, when a small, unremarkable pebble altered the afternoon.

There was a sharp report — like a champagne cork fired by Providence — and my rear tyre expired with theatrical finality.

Trevor braked, turned, and coasted back, his shadow looping behind him. “Blowout?”

“Indeed,” I said, with a calm born of despair. “But not to worry. I’ve read extensively on the subject.”

I dismounted, removed my jacket, and began loosening the wheel. On ordinary occasions, I enjoy the illusion of mechanical mastery. On this one, the machine resisted like a mule with a union card. The rear chain assembly was a puzzle in blackened steel; the cable to the gears seemed to have taken holy orders and refused release.

“May I?” said Trevor, stooping.

“Thanks, but I can manage this on my own.”

He accepted that — and wisely. Within minutes my hands were a study in soot and blasphemy. Grease printed itself on my shirt cuffs, my cheek, and one especially theatrical streak across the bridge of my nose.

Trevor, whose faith in my competence had limits, glanced downhill and pointed. “That wall — do you see? Possibly twelfth century. A mill, perhaps, by the stream.”

“By all means,” I said, wrestling the rear axle. “Go commune with antiquity.”

He trotted off down the embankment, sketchbook in hand, leaving me to my contest with metallurgy. The air was still, cicadas holding their breath. I had just freed the wheel with a small cry of triumph when movement up the road caught my eye — a lone cyclist descending through the heatwaves, the sun behind it so that it appeared momentarily as a figure of fire and shadow.

It was a woman, riding with the self-possession of someone who knows she is being watched by the century. As she drew closer the mirage resolved into form — khaki slacks, wide-legged and cuffed, a narrow waist caught by a white shirt knotted above the belt. A ribbon bound her right trouser leg to spare it from the chain. She wore a small beret and a smile both continental and completely disarming.

“Bonjour!” she called as she drew to a halt beside me. “Can I be of assistance?”

“Well, actually, yes,” I managed. “I seem to have misplaced my, ah—”

“You mean your tire lever,” she said, producing one from her kit with the grace of a conjurer.

“That’s the term,” I said. “Quite slipped my mind.”

She knelt beside the bicycle, sleeves rolled just so, and proceeded to remove the tyre, patch the tube, and reseat the wheel with the serene precision of a surgeon at a matinée. Not a fleck of grease found her cuffs. When she tightened the chain and spun the wheel, it purred in gratitude.

“Voilà,” she said. “You may proceed to conquer France.”

“Not without your name,” I said.

“Monique.”

Of course it was. There are names that feel rehearsed by the landscape; hers was one of them. She mounted her bicycle — a sleek black Peugeot — and smiled. “Perhaps we ride together a little? It is better, no, to have witnesses to our success?”

Trevor reappeared, wiping dust from his knees, just in time to see her turn the pedals with unstudied grace. “Good heavens,” he murmured. “You’ve summoned Aphrodite on a touring cycle.”

“I did mention I was mechanical,” I said.

We rode three abreast for the rest of the afternoon, the canyon widening, the light turning honey-coloured. Conversation drifted between French and laughter. Monique knew the road to Uzès, the history of half its bridges, and where to find a decent claret that travelled well in a flask. She was, in short, the answer to a question I hadn’t known I’d been asking.

That evening, at an inn near the river, Trevor dined alone, claiming exhaustion and the need to “catalogue one’s impressions.” Monique and I took a bottle to the terrace and watched the last sun fall behind the poplars. What followed was not the sort of thing one records in a field notebook, but I recall thinking that even empiricism had its limits.

Morning revised the romance. Her side of the bed was empty. My wristwatch, wallet, notebook, and the annotated map of our route were gone. The sheets smelled faintly of lavender and irony.

I found Trevor downstairs, breakfasting with untroubled conscience. “She’s left you?” he asked mildly.

“With most of my worldly goods,” I said.

He poured coffee. “Lawrence would have admired her efficiency.”

Chapter V — The Weather Improves

“There is something knightly in this solitude — a sense that the road itself is a companion, impartial and severe.” — T. E. Lawrence, letter to his mother, 1908

Morning came as though apologising for the night. The storm had scrubbed the sky to a chastened blue, and the inn’s geraniums looked newly repentant. Trevor appeared at breakfast with a bandaged wrist and the moral certainty of a man whom history has merely jostled.

“The custodian,” he said, “wasn’t angry after all. She said she admired our devotion.”

“Ah,” I said, “devotion—the French word for trespass.”

He ignored the slander, as he always does when it concerns his better nature. “And the inscription, Duffy—those initials. Even if it was another hand, we’ve proved the legend could be true. That’s the point of inquiry: to give fact its chance.”

I buttered a croissant with scientific precision. “We’ve certainly given it every chance of escape.”

Trevor laughed and lifted his coffee in a toast. “To Lawrence, who left us something to find.”

“To the custodian,” I said, “who left us something to pay.”

We settled accounts with the innkeeper, who informed us that a group of German tourists had also gone to see Roquetaillade that morning but “would be using the proper entrance.” Trevor said he envied their innocence. I envied their sense of direction.

Outside, the air smelled of vines and wet earth—the sort of morning that makes you forgive civilisation for inventing breakfast. We wheeled our bicycles into the sunlight. The tyres steamed gently, as if remembering the previous day’s adventure.

Trevor examined the map, now a wrinkled palimpsest of good intentions. “Arles next,” he declared. “Lawrence turned east after this. We’ll follow his wheel tracks along the Rhône valley. Imagine—the castles of Provence, the Roman walls, the light that drove Van Gogh mad!”

“Excellent,” I said. “Perhaps we’ll find him on the return journey, painting the view of us leaving.”

Trevor looked up from the map, a glint of mischief in his eye. “If you’re writing up our journey, Duffy,” he said, “you might dedicate the chapter to the lady of the canyon.”

I pretended to consider it. “Yes. A footnote, perhaps — on the hazards of fieldwork.”

He smiled. “Romance is fieldwork, in your case.”

“Then I shall record it under ‘erosional features,’” I said, and we both laughed — which seemed the only civilised response to experience.

Trevor laughed, which was all the victory I required. We set off, the road glistening like a newly written sentence. The vineyards fell away, and the horizon opened to its usual conspiracy of promise.

After a few miles, we dismounted at a wayside café to take bearings. The proprietor recognised our mud-stained knickerbockers as a sign of either eccentricity or scholarship and brought two glasses of white wine without being asked. He studied our bicycles approvingly.

“Long road ahead, messieurs?”

“Not as long as the one behind,” I said.

Trevor raised his glass. “To the Middle Ages—still pedalling.”

I raised mine. “To the present—trying to keep up.”

The sun climbed; the wine declined. We mounted our bicycles and resumed the pilgrimage, our shadows riding slightly ahead as if to scout the next absurdity.

Duffy’s journal closes the entry there, with one final observation pencilled in the margin:

“The difference between a knight and a tourist is the rate of recovery.”

—Duffy Whitmore

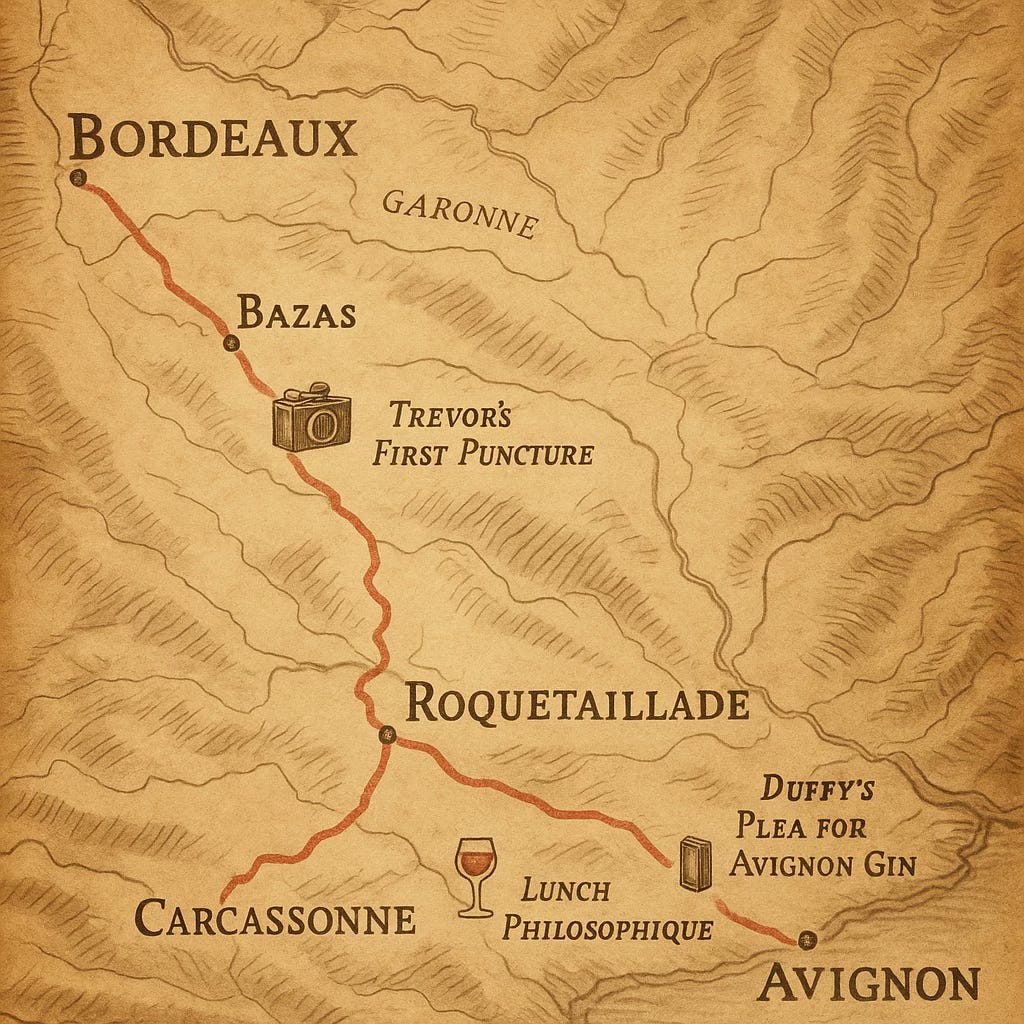

Postscript — A Note on the Route

Map of Southern France, showing the route of T. E. Lawrence’s 1908 cycling expedition, as later retraced by Trevor Finch-Bligh and the present writer. Drawn from conjecture, hearsay, and the recollections of several waiters, this chart should not be relied upon for distances, gradients, or sobriety. The winding red line represents the general direction of enthusiasm rather than topographical fact.